As I hem and haw my way toward my next writing project, I have taken several swipes at an outline. I’m an outliner, yes. Without an outline, I’m writing word salad into a desert. I don’t always follow my outline, but I need a rough map at least.

As I hem and haw my way toward my next writing project, I have taken several swipes at an outline. I’m an outliner, yes. Without an outline, I’m writing word salad into a desert. I don’t always follow my outline, but I need a rough map at least.

Over the years I’ve developed a generic outline template designed mainly to keep the pace. Certain key scenes are necessary in any novel I write. In principle, I could write those ten or twelve key scenes first then connect the dots, but I’ve never done that. Doesn’t feel right to me.

I’m especially concerned to avoid the mid-belly sag that often occurs in Act 2, so this outline is specific about how major scenes are distributed. It tends to be front-loaded, because even though I personally prefer a long, subtle lead-in, most readers don’t. The times we live in demand immediate developments.

Also, the wrap-up, in Act 3 seems truncated by stuffing it into the last 25% of the story, but that’s also what readers like: a ka-bam! ending.

I think the outline will work for genre fiction as well as literary (character-driven). The main difference is whether the story drivers are “in the world” or “in the gut.”

I tend to write short novels, 72K to 75K words because that’s about all the attention span I have. I try to, as Elmore Leonard advised, “leave out the parts that readers skip.” But you could apply the pacing percentages to 100,000 words just as well.

Is it formulaic? Of course. But it’s just a framework, not the finished house. I’m already thinking of how the story I have in mind will not follow this outline. Still, I will use it to get me started and lead me forward and alert me to dreaded pace sag.

The structure this template shows could be mapped into a visually graphic format, as long as the proportions for each “bubble” were conserved.

Abbreviations Used: PP=Plot Peak; ANT=Antagonist. AP=Ant-Point. MC=Main Character. RI=Romantic Interest. RC=Reaction Character. SQ=Status Quo. Hamartia = hidden weakness or secret shame; MC’s Achilles’ heel. WOM= a main advisor (“Wise old Man” or other). NLT= No later than. PN=Narrator. %= proportion of total projected page or word count to maintain a good pace. Italic highlight = Landmark Scene that cannot be skipped.

0% Act 1. Setup, Intro MC with opening image. Shows MC’s world and character. MC reacts to a small, foreshadowing conflict which is also a hook. Not the trigger, but something is not right. Patch it over while revealing the theme and the character of MC. Show MC’s dominant trait and hidden need (hamartia); the inner demons. Show but don’t explain.

10% NLT. Trigger event Disrupts (upends) the SQ; Rocks the world. Trigger is exogenous to MC but specific to MC, not generic. MC’s reaction sets the plot in motion. Define the Story goal. What does MC WANT, specifically?

15% MC’s Initial Reaction to trigger is a failure, makes things worse. Confusing. Introduce or hint at ANT by way of explanation of the failure.

20% Rubicon. PP1 Basic conflict is clear. MC is over his or her head, acts irreversibly though it doesn’t seem so at the time (e.g. cheats, breaks law, crosses the river, etc.) A point of no return. Story path is set for MC: Get the MacGuffin, escape the threat, save the farm, do your duty, begin the journey.

25% NLT Act 2. Response phase. MC is victim of slings and arrows (and own hamartia). MC acts repeatedly to fix SQ, often overconfident, and fails. Obstacles and complications are self-generated. Romantic story begins often badly. RI is diffident or offended.

30% MC is bewildered.Each response sets up the next obstacle. MC is digging his or her own hole, walking into it, but doesn’t realize. AntP1 point. Ant is clearly revealed and personified (not abstract). Romantic story shows signs of hope.

40% Complications. Stakes go up. Potential for loss is greater than formerly realized. It’s serious. MC suffers failure, pain and loss. Is afraid. MC can’t go back, can’t see forward. Romantic relationship is on the rocks. Escalation continues. MC tries harder; fails again.

50% Midpoint. Turning point. Some hope is seen. The romance recovers tentatively. New info or resource comes to light and a plan becomes possible. MC goes on the offensive for the first time. Hopes are high. Despite best efforts, big plan fails. Hope is dashed. Precious resources are lost. No Plan B. No other options apparent. Disaster.

55% The Pit. Romantic and other relationships break down, in anger, disappointment, misunderstanding, etc. MC discouraged. Doubts self. Questions goals. RC advises courage, perseverance but MC is wracked with fear and doubt.

60% AntP2. We need a bigger boat moment. ANT appears in full strength and wins a major skirmish, ups the ante. Seemingly insurmountable obstacle arises. The problem is much larger than previously thought; overwhelming.

65% Rock Bottom. Ant prevails. Dark night of the soul. MC is ruined, Alone and near death. MC Despairs. MC gives up and wanders off. Quits the field. Leaves the project, abandons the story goal. Complete Failure is realized, Only ashes left;

70% The turn: PP2, Critical Choice. MC hears from RC, RI, or gets advice from WOM; or, MC takes unexpected inspiration from an insignificant and odd thing, something that might have been planted earlier unnoticed; a special device, a memory, a person, a risky passage or technique. MC decides to go with that, despite the inner demons. MC plans a desperate chance a seemingly mad, irrational decision that goes against type. What the hell, do the right thing moment. Possibly against advice of RC, RI.

75% NLT Act 3. Confrontation. MC arranges a situation to confront ANT. Sets it up. RI may be at risk. Can withhold information from reader, showing only the setup.

85% Climax. Big showdown. White vs black hats as MC confronts ANT. MC prevails (which was not guaranteed) or dies. MC triumph (or noble death). But the story goal is achieved. RI is won.

95% Character Reversal. MC is a new person (or martyr). MC has overcome ANT, achieved the story goal and has possible epiphany. Understands the hamartia (need not be spelled out). Solid relationship with RI.

<100% Resolution Mirrors the opening image but in a new SQ. Nothing will ever be the same again.

100% ###END###

Developed by Bill Adams from various sources. http://billadamsphd.net.

Looking through my NBT (Next Big Thing) list, I find dozens of attractive ideas for a new novel. I notice many of them would fall into the category of “speculative fiction,” which I believe is mostly realism, but with some fantastic “what-if” element that drives the story.

Looking through my NBT (Next Big Thing) list, I find dozens of attractive ideas for a new novel. I notice many of them would fall into the category of “speculative fiction,” which I believe is mostly realism, but with some fantastic “what-if” element that drives the story. I have a collection of family snapshots scanned into the computer, going back to 1945. It’s mostly pictures of and by me. The traditional photographic records that a family might have going back across the generations, I don’t have and maybe never existed. Photography is a leisure activity not high on the priority list for immigrants and working-class people. My family didn’t take many pictures, and most of the ones we did have were lost in a flood during the 1960’s. I have the salvage from that, plus my own snapshots since then.

I have a collection of family snapshots scanned into the computer, going back to 1945. It’s mostly pictures of and by me. The traditional photographic records that a family might have going back across the generations, I don’t have and maybe never existed. Photography is a leisure activity not high on the priority list for immigrants and working-class people. My family didn’t take many pictures, and most of the ones we did have were lost in a flood during the 1960’s. I have the salvage from that, plus my own snapshots since then. I reread my notes on Swann’s Way, Volume one of Proust’s novel, In Search of Lost Time. I read reviews of several scholarly books on the topic of “memory studies,” a field that likes to analyze the social meaning of photographs. And I wrote five thousand words of notes. And I still have nothing. So, much to my surprise, this may not be the basis for a project after all.

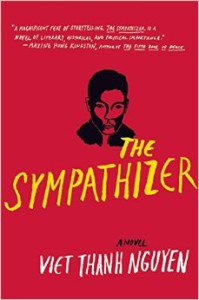

I reread my notes on Swann’s Way, Volume one of Proust’s novel, In Search of Lost Time. I read reviews of several scholarly books on the topic of “memory studies,” a field that likes to analyze the social meaning of photographs. And I wrote five thousand words of notes. And I still have nothing. So, much to my surprise, this may not be the basis for a project after all. Interesting writing kept the pages turning for me. Nguyen has a knack for unexpected description and creative simile. A random example: Two men are talking but notice the chairs:

Interesting writing kept the pages turning for me. Nguyen has a knack for unexpected description and creative simile. A random example: Two men are talking but notice the chairs: Since the Brexit vote, in which Britain decided to leave the EU, many hands have been wrung. Nevertheless, it doesn’t seem like much communication has occurred. The losing “Remainers” genuinely don’t seem to get the message. They view the Brexit vote as an error.

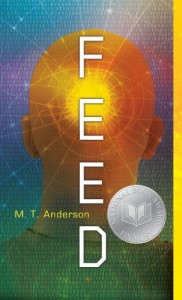

Since the Brexit vote, in which Britain decided to leave the EU, many hands have been wrung. Nevertheless, it doesn’t seem like much communication has occurred. The losing “Remainers” genuinely don’t seem to get the message. They view the Brexit vote as an error. This sci-fi novel is addressed to “young adults” defined as aged 14 and up. It was recommended to me for reasons I can no longer remember. I don’t read or write YA fiction, so I have to give allowance for a domain I am not very familiar with, but I have to say, this book seemed heavy-handed, simplistic, pandering, obvious, and downright insulting to any 14-year-old with the intelligence and motivation to read a sci-fi novel. It’s been a long time since I was fourteen, but I can’t imagine I would ever have found a book like this enjoyable. That said, the book is a National Book Award Finalist, so I’m the odd one out.

This sci-fi novel is addressed to “young adults” defined as aged 14 and up. It was recommended to me for reasons I can no longer remember. I don’t read or write YA fiction, so I have to give allowance for a domain I am not very familiar with, but I have to say, this book seemed heavy-handed, simplistic, pandering, obvious, and downright insulting to any 14-year-old with the intelligence and motivation to read a sci-fi novel. It’s been a long time since I was fourteen, but I can’t imagine I would ever have found a book like this enjoyable. That said, the book is a National Book Award Finalist, so I’m the odd one out. On a recent business trip I stole a few days of vacation at La Jolla, in southern California, with my wife. We walked on the cliffs and the beaches and talked to the barking seals and we watched a man die right in front of us.

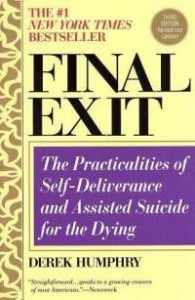

On a recent business trip I stole a few days of vacation at La Jolla, in southern California, with my wife. We walked on the cliffs and the beaches and talked to the barking seals and we watched a man die right in front of us. Everyone dies. A significant number of people will die in automobile crashes, gang wars, from drugs, or in military wars, but because of modern medicine and public health, if you live through your twenties, you’ll probably die of “natural causes,” which is to say, of the diseases that come with old age. And how does that go? Usually not well.

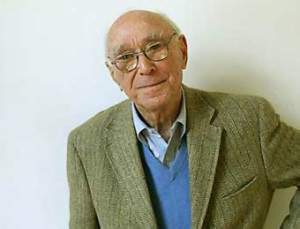

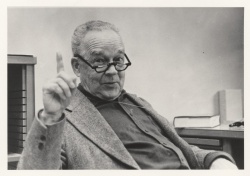

Everyone dies. A significant number of people will die in automobile crashes, gang wars, from drugs, or in military wars, but because of modern medicine and public health, if you live through your twenties, you’ll probably die of “natural causes,” which is to say, of the diseases that come with old age. And how does that go? Usually not well. Jerome Bruner died recently at age 100. He was one of the first cognitive psychologists. His 1956 book, “A Study in Thinking” (co-authored with two other ground-breaking psychologists, Jacqueline Goodnow and George Austin), was the first shot fired in the cognitive revolution that finally overturned behaviorism. It demonstrated that minds could be studied scientifically. Others had done that before, people such as Fechner and Ebbinghaus in the 1800’s, but for some reason it was the Bruner, et al. book that made the splash. Right place at the right time, no doubt. You can’t fight history.

Jerome Bruner died recently at age 100. He was one of the first cognitive psychologists. His 1956 book, “A Study in Thinking” (co-authored with two other ground-breaking psychologists, Jacqueline Goodnow and George Austin), was the first shot fired in the cognitive revolution that finally overturned behaviorism. It demonstrated that minds could be studied scientifically. Others had done that before, people such as Fechner and Ebbinghaus in the 1800’s, but for some reason it was the Bruner, et al. book that made the splash. Right place at the right time, no doubt. You can’t fight history.![Stimulus_2_materials[1]](http://billadamsphd.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Stimulus_2_materials1-300x225.jpg) The Bruner book was on “concept formation,” something that a mind does, not the behaviorists’ muscle-twitches. Volunteers viewed complex geometric displays on cards, for example a yellow circle containing a single digit, enclosed in a green triangle. They were told if that item was a member of the target class or not. After viewing a series of such samples, the volunteer had to describe the target class, what it included and excluded. It could be, for example, even numbers inside squares. In order to form the correct concept, the volunteer would have to infer what all the positive examples had in common, and that the “wrong” samples lacked.

The Bruner book was on “concept formation,” something that a mind does, not the behaviorists’ muscle-twitches. Volunteers viewed complex geometric displays on cards, for example a yellow circle containing a single digit, enclosed in a green triangle. They were told if that item was a member of the target class or not. After viewing a series of such samples, the volunteer had to describe the target class, what it included and excluded. It could be, for example, even numbers inside squares. In order to form the correct concept, the volunteer would have to infer what all the positive examples had in common, and that the “wrong” samples lacked. In my post-doctoral research year, studying with psychologists James and Eleanor Gibson at Cornell, Bruner’s name came up often. They disliked him and everything he stood for. Professional rivalry is the norm, but both Gibsons often disparaged Bruner in front of students. Why would you do that? That’s beyond friendly competition.

In my post-doctoral research year, studying with psychologists James and Eleanor Gibson at Cornell, Bruner’s name came up often. They disliked him and everything he stood for. Professional rivalry is the norm, but both Gibsons often disparaged Bruner in front of students. Why would you do that? That’s beyond friendly competition. The first two chapters of this slim volume were most helpful to me. “What is science-fiction?” is not an easy question, especially in distinguishing it from fantasy and the broader category of speculative fiction. Basically, Card says sci-fi concerns experience that is not yet possible but is technologically or theoretically on the horizon, whereas fantasy is never going to happen (dragons, wizards, etc.). In Speculative fiction, the author proposes an idea or MacGuffin, and the story is the unfolding of all its ramifications.

The first two chapters of this slim volume were most helpful to me. “What is science-fiction?” is not an easy question, especially in distinguishing it from fantasy and the broader category of speculative fiction. Basically, Card says sci-fi concerns experience that is not yet possible but is technologically or theoretically on the horizon, whereas fantasy is never going to happen (dragons, wizards, etc.). In Speculative fiction, the author proposes an idea or MacGuffin, and the story is the unfolding of all its ramifications.