I bought and read this book prior to attending a seminar led by Mr. Brooks. The workshop was far better than the book. The book can be useful but has extremely low information density. Mainly it is a ranting manifesto against muse-driven, spontaneous, seat-of-the-pants writing (as advocated by Stephen King and many poets), and in favor of promoting careful story planning (engineering), before you start writing your novel.

I bought and read this book prior to attending a seminar led by Mr. Brooks. The workshop was far better than the book. The book can be useful but has extremely low information density. Mainly it is a ranting manifesto against muse-driven, spontaneous, seat-of-the-pants writing (as advocated by Stephen King and many poets), and in favor of promoting careful story planning (engineering), before you start writing your novel.

Brooks’s planning schema is a mini-beat sheet in word count or page number or screen-minute quartiles: 1. The Setup, in which the main character is introduced and the status quo (SQ) is established. This section ends with the “first plot point” or trigger incident, which upsets the status quo, forces the MC to react, and sets the story in motion. 2. The Response section shows the MC responding to the trigger and reveals the antagonist or obstacle (Ant). The MC struggles but fails to overcome the Ant. This section ends at the Midpoint, during which MC switches from defensive reactions to attack mode. 3. The Attack section shows MC gathering strength from a strategy for overcoming the Ant. However, the MC usually suffers a devastating failure first and hits bottom as Ant becomes ascendant. The section ends with the second plot point, in which MC discovers new information or resources that allows him to prevail. 4. In the Resolution section, MC does prevail over Ant and reestablishes a new SQ.

That is a useful outline for many stories. It’s a variation on the “three-act structure” of a screenplay. Brooks divides the traditional second act into his sections 2 and 3, which is helpful to a writer for avoiding the curse of the saggy middle.

In the seminar I took with Brooks, he attempted to tone down the arrogance apparent throughout his book but he still ranted (politely, but unyieldingly) against anyone who disagreed with him in any way. He explained the four-part structure and virtually commanded writers to use it in planning and to retrofit their existing first drafts into his schema.

In my class of 20 novel writers about a dozen attempted to explain their story outline in terms of Brooks’s schema and not a single one could do it. This is not the fault of the outline, which is solid. The problem is that most writers are wedded to their story and even when they praise and espouse Brooks’s template, they are unable to separate form from content. By the last day of the workshop, he had given up and simply praised any story that cohered better than a word salad. I felt sorry for him.

Part of the problem is that Brooks’s outline is designed for the contemporary thriller, not so much for other genres, despite what he claims about its universality. Some stories are road trips, picaresques, reminiscences or episodes (Olive Kitteridge, for example). It doesn’t even fit a traditional mystery format very well.

Brooks is focused on how to become a “best-seller” and make a lot of money writing a hit novel and he thinks (probably rightly) that the easiest path to that goal is to write the next runaway hit thriller. But not everyone wants that.

He emphasizes that you must have a “killer concept” for your novel, a compelling idea that will immediately grab the reader (Snakes on a Plane!). It doesn’t occur to him that some writers use the novel as an art form to explore what it means to be human (Remains of the Day, for example). How some improbably contrived, fictional serial killer gets caught is of zero interest to such a writer.

Brooks seems to have no concept of contemporary literary fiction, which he disparages relentlessly. He apparently thinks literary fiction means flowery, purple prose, Henry James, perhaps. Not surprisingly, none of his examples are from literary fiction. All are from contemporary thrillers. That was a disadvantage for me, as I am not well-attuned to popular culture, and not at all to popular television series, so I was as unfamiliar with the examples he cited as he was with the kind of books I’m interested in (e.g., Faulkner, Strout, Ishiguro, Vonnegut, Pynchon, Woolf, Nabokov, Flanagan, De Lillo, Alexie).

In the few cases where I was familiar with his favorite authors (Dan Brown, James Patterson, Nelson DeMille, Andy Weir), they were without exception books and authors I have tried to read but have been unable, so badly were the works written, or so contrived and banal the stories. Brooks and I are apparently from different reading and writing planets.

Brooks also does not discriminate between the novel and the cinema form of storytelling, which are quite different. The main (only?) advantage of the novel form is its ability to explore the inner life of the characters, something difficult to do in cinema. His recommended method of writing is entirely external and objective, as defined in his template. Naturally then, a flat, visual, action-oriented story is his idea of perfection.

Brooks gives only the most superficial lip service to character development. He vaguely references the MC’s “inner demons” but has nothing to say about what role those play in the development of the story. He talks about “resolving” the story, as in a Grisham drama, but doesn’t mention epiphany, reversal, or catharsis.

In his book and in the seminar, Brooks lists (as an afterthought — it does not appear in his schema) the character’s development, but by that he means only the causal sequence of the story line. For example, at the midpoint, MC switches from victimized responder to aggressive attack mode. Why? No reason at all. That is simply what happens at the midpoint. Perhaps MC gets a second wind.

In his pseudo-explanation of “character development” Brooks gestures vaguely to a Joseph-Campbellesque list of archetypal roles, as if that covered it. He has nothing to say about how the character’s development drives the story – apparently because he sees the character arc as superfluous to the story line, which is entirely objective.

Brooks’s idea of “story” seems to be any marginally plausible causal sequence of events acted out by characters. Another definition, dating from Aristotle’s Poetics, is an account of how a character learns something about the relationship between self and world (or self and other). The classic example is Oedipus Rex. Brooks’s ideal characters are unreflective, too busy bashing bad guys to learn anything (e.g., Superman). I admit most readers (and book-buyers) prefer a Brooksian character and a Brooksian story, but that’s no excuse for being a dogmatic writing teacher.

Despite these shortcomings and the gratingly one-sided presentation of the ideas, I learned some valuable tips. I believe that literary fiction, to which I aspire, needs stronger story structure, and I believe it is possible to blend Brooks’s story engineering template with other approaches that focus on the character arc, with the result of an artistic and memorable story (if not a best-seller).

I feel that I have gone into the lair of the enemy, snatched a small treasure, and escaped undetected. It’s good to know what the Earthlings are thinking.

Brooks, Larry (2011) Story Engineering. Cincinnati, OH: Writers Digest Books.

This booklet offers advice to writers about point of view. It defines POV as a “position” from which something is considered or evaluated (p.6). The author eventually explains that this “position” is not a spatial location (e.g., a camera placement in cinematography), but instead, the psychology of whichever character is telling the story at any given moment.

This booklet offers advice to writers about point of view. It defines POV as a “position” from which something is considered or evaluated (p.6). The author eventually explains that this “position” is not a spatial location (e.g., a camera placement in cinematography), but instead, the psychology of whichever character is telling the story at any given moment.

A colleague, Skylar Kahn, once met Isaac Asimov and subsequently wrote an interesting rememberance of one his speeches from the 1970’s (www.copperarea.com/pages/isaac-asimov-womans-role/). The theme of population growth concerns me and inhabits my latest sci-fi novel in progress.

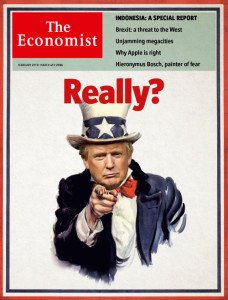

A colleague, Skylar Kahn, once met Isaac Asimov and subsequently wrote an interesting rememberance of one his speeches from the 1970’s (www.copperarea.com/pages/isaac-asimov-womans-role/). The theme of population growth concerns me and inhabits my latest sci-fi novel in progress. News media are abuzz with stories of how the establishment Republican party is desperate to stop Trump from getting the presidential nomination. Why? Because he’s supposed to be a flawed character, vulgar and duplicitous, intellectually vapid, and ill-suited for the office. I can’t disagree.

News media are abuzz with stories of how the establishment Republican party is desperate to stop Trump from getting the presidential nomination. Why? Because he’s supposed to be a flawed character, vulgar and duplicitous, intellectually vapid, and ill-suited for the office. I can’t disagree. Phoenix, Arizona is not very coastal but

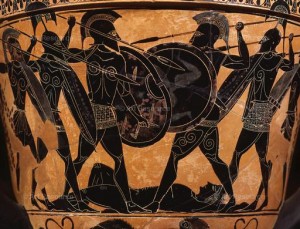

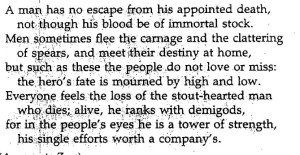

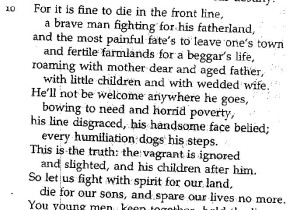

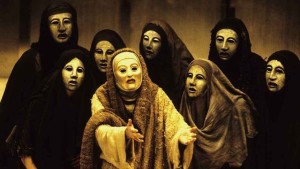

Phoenix, Arizona is not very coastal but I’ve been reading ancient Greek tragedies by Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, and other poets, and trying to wrap my head around a culture that celebrated war and glorious death in battle. It was the unquestioned and unquestionable fate of healthy young men (and they all were healthy, because the ancient Greeks practiced infanticide).

I’ve been reading ancient Greek tragedies by Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, and other poets, and trying to wrap my head around a culture that celebrated war and glorious death in battle. It was the unquestioned and unquestionable fate of healthy young men (and they all were healthy, because the ancient Greeks practiced infanticide).

The first chapter of this novel was brilliant and won me over. A sophisticated city couple retreats to their country cottage in England, where they try to be friendly with the country-bumpkin neighbors who own an estate, and significantly, several old paintings they’d like to have evaluated.

The first chapter of this novel was brilliant and won me over. A sophisticated city couple retreats to their country cottage in England, where they try to be friendly with the country-bumpkin neighbors who own an estate, and significantly, several old paintings they’d like to have evaluated. I recently finished the tenth revision of my cop thriller novel. I’ve been working on it for five years. It’s been through a million cuts and folds. The original is no longer even recognizable in it, and I thought I had finally gotten it right. So I submitted it to my critique group, a wonderful gang of fellow-writers. Five of them signed up for the read.

I recently finished the tenth revision of my cop thriller novel. I’ve been working on it for five years. It’s been through a million cuts and folds. The original is no longer even recognizable in it, and I thought I had finally gotten it right. So I submitted it to my critique group, a wonderful gang of fellow-writers. Five of them signed up for the read. Recently I’ve been reading some of the classical Greek plays, notably Aeschylus: Agamemnon, The Persians, and Seven Against Thebes; Sophocles: Ajax. I took a couple of Classics courses in college and enjoyed them, and this re-visit broadens my understanding.

Recently I’ve been reading some of the classical Greek plays, notably Aeschylus: Agamemnon, The Persians, and Seven Against Thebes; Sophocles: Ajax. I took a couple of Classics courses in college and enjoyed them, and this re-visit broadens my understanding.