My Galaxy 42mm black “smartwatch” was a fun toy, but I took it back after two weeks. Best Buy made the refund easy, no questions asked. That’s one reason I bought it there. Also they had the best extended warranty, which you need on a product this new and complicated. Theirs was a simple “replace” warranty, vs. “repair” and “best effort” warranties at other dealers. The price was about the same as everywhere, maybe $25 lower, but that was not a factor. These “smartwatch” gizmos are way expensive. You just have to get past that if you want one.

My Galaxy 42mm black “smartwatch” was a fun toy, but I took it back after two weeks. Best Buy made the refund easy, no questions asked. That’s one reason I bought it there. Also they had the best extended warranty, which you need on a product this new and complicated. Theirs was a simple “replace” warranty, vs. “repair” and “best effort” warranties at other dealers. The price was about the same as everywhere, maybe $25 lower, but that was not a factor. These “smartwatch” gizmos are way expensive. You just have to get past that if you want one.

So why did I take it back? Two reasons. 1. It didn’t do what I wanted. 2. It did do what I didn’t want.

The main reason I wanted a smartwatch was to give me notifications on my wrist when I receive phone, email, or text messages on my phone, which is usually in my pocket. Half the time I miss the notifications from the phone even with the volume turned up, and sometimes I’m in a meeting or in a class and I have the ringer volume low. Getting a “bzzzt!” on my wrist is a perfect, unobtrusive way to stay connected. (This says something about how clunky phones are).

My Galaxy watch didn’t reliably give me the notifications I wanted. Sometimes it just didn’t do it at all.That was especially true for text messages. I pored over the settings and experimented endlessly. The watch did pick up all phone calls and most of time, email. Samsung privileges its proprietary messaging and email apps, which I don’t use. I use Google for both. I have to wonder if that was part of the problem. I tried turning all notifications off then going back in and selectively turning on the key ones. I also tried the reverse procedure. Nothing worked reliably. “Sometimes” is not good enough.

Also, when I did get a notification on the wrist, I did not know what it was for. I’d check the notices screen by clicking the very cool bezel interface, and would find a message that said something like “Check your settings on your phone.” Which I did, finding nothing. The watch correctly reported phone calls, but not always text or email. It was possible to go into the Google mail app and scroll through those, but that’s not what I wanted. I wanted notification when something came in.

The second major problem with the watch was a blizzard of notifications. The thing was buzzing with irrelevant notifications all day, nearly all of them from Samsung’s built-in “health” apps. For example, I got a “notice” whenever I sat at my computer for an hour without getting up to walk around. Who asked for that? I was unable to turn it off. Likewise for all the dozens of other health apps, like heart rate, calories burned, steps walked, stairs climbed, kilometers run. Buzz, buzz, buzz, all day. I learned how to turn off most of those but not all. The app names often had little relation to what they measure, and there were literally dozens of them, combinations and extensions of data from basic sensors such as heart rate monitor, pedometer, and altimeter.

If I wanted a basic health watch I could have bought a Fitbit for a fraction of the price. Since I recently was discharged from a hospital event, I confess I have not been climbing a lot of stairs or running a lot of kilometers. I’m happy to be breathing. My watch became a relentless nag annoying the heck out of me. I could not control the notification settings. One notification, for example, is simply called “Samsung Health” I couldn’t guess what that entails. (Documentation is useless).

Finally, there was the stupidity factor. I could not use the “sleep monitoring” app because I had to put the watch on its charger overnight. Each day the battery would run down to about 35% by bedtime, not enough left to get through the night, and even if it did, it would be dead in the morning. The charging cradle is very easy to use.

The much-advertised four-day battery life should be taken with a large grain of salt. That figure is advertised for the 46mm watch, which has a larger battery. I could find no specific claim for battery longevity for the 42mm version but my experience was that it comfortably lasts a full day, but not 24 hours.

In any event, each morning when I put the watch back on, it would immediately report on my “sleep efficiency” whatever that might be (What is inefficient sleep?). I’m proud to report that my sleep efficiency was always in the high nineties, even though the watch was in its charging cradle all night. Maybe it meant its own sleep efficiency?

Another stupidity occurred in trying to download and use additional apps. Apps must run on Samsung’s proprietary Tizen operating system and they are few and primitive and generally not free, and overpriced. For example, I wanted a simple countdown timer with an alarm I could control, for timing meetings and movies. The free offering from Samsung was flawed and had terrible reviews. Others in the store were exorbitantly priced. I found a competent free third-party offering, downloaded it, and never saw it again. It had no widget and did not appear on any Samsung display of apps. I had no idea where it had gone or how to get to it. I had the same experience with several small utility apps, such as for a compass, a flashlight, and a calculator.

I should note that an enthusiastic user of this watch could do more with it than I did. It will, for example, allegedly send and receive phone calls in “Dick Tracy” mode, provided you sign up for a separate phone account with Verizon or other wireless provider. I had no need.

The watch also supports making payments as long as you use “Samsung Pay” (it won’t do Google Pay or Apple Pay), and you don’t mind having your credit card information loaded into your phone/watch, and you have some kind of a problem with cash or plastic payments. It was not for me.

Fooling around with the various watch faces was kind of fun, I admit. I enjoyed the sheer creativity of the various designs, from analog to digital, to purely verbal, animated, graphic, artistic, and much else. The range of offerings made me reconsider “What is a clock, anyway?”

Most of them however were not readable at a glance, my main requirement, and 99% of the free ones were not customizable, so in reality, the list of practical choices was quite limited. But I did find a half-dozen that I liked. They all behaved differently, and I wondered how one’s choice of watch face interacts with the notification systems I struggled with. You would think those two things would be independent, but there is no way to know.

Incidentally, I ended up keeping my watch face “on” all the time because it was extremely annoying to glance at the watch and stare stupidly at a black screen until the watch face came “on” – admittedly after a second or less, but in psychological time, that was forever. So I selected “always on” mode, sacrificing a little battery performance to the spirit of Bishop Berkeley (“To be is to be perceived.”).

It turns out, though, that “always on” really means that when you’re not looking, the watch face is in a reduced power mode, dim and minimized, but not fully on. Nevertheless the result was that when I rotated my wrist up to get the time, it came on much faster, with a delay that was merely annoying rather than infuriating.

After two weeks and many hours of fussing and learning, I decided that my not-so-smart watch was more trouble than it was worth and took it back. I think this is a technology before its time. In three to five years I’ll look again. For now I’m again wearing my $75, analog “Swiss Army” watch from Costco. It doesn’t report my heart rate, but it’s always on when I look at it, day or night.

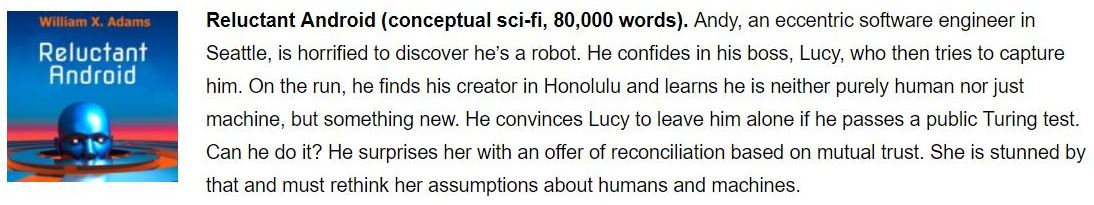

Reluctant Android is now available for pre-order as an ebook from Amazon and Smashwords.

Reluctant Android is now available for pre-order as an ebook from Amazon and Smashwords. Careers have been built on mining the depths of The Great Gatsby, that most iconic of American novels. I recently read it for the third time to see what I could learn about the craft of writing.

Careers have been built on mining the depths of The Great Gatsby, that most iconic of American novels. I recently read it for the third time to see what I could learn about the craft of writing. Finally, my new site featuring my psi-fi books is up. (

Finally, my new site featuring my psi-fi books is up. (

You don’t expect much drama from anthropologists in the jungle, but the members of this trio divide their angst between their simmering and barely acknowledged love triangle and their understanding of pre-industrial river people of New Guinea in the 1930’s.

You don’t expect much drama from anthropologists in the jungle, but the members of this trio divide their angst between their simmering and barely acknowledged love triangle and their understanding of pre-industrial river people of New Guinea in the 1930’s. This is the autobiographical story of a holocaust survivor, Hungarian writer and Nobel Prize-winner, Imre Kertesz. To me, it is reminiscent of Primo Levi and even Victor Frankl.

This is the autobiographical story of a holocaust survivor, Hungarian writer and Nobel Prize-winner, Imre Kertesz. To me, it is reminiscent of Primo Levi and even Victor Frankl. This book is a good value at under $30 because it is actually three books. The first is for beginners, the second, for “intermediate” students of the blues, and the third for “mastering” blues guitar. I mean, it is literally three books, each by a different author, with three separate tables of contents. There’s enough material to keep anyone busy for a very long time. But for me, it didn’t.

This book is a good value at under $30 because it is actually three books. The first is for beginners, the second, for “intermediate” students of the blues, and the third for “mastering” blues guitar. I mean, it is literally three books, each by a different author, with three separate tables of contents. There’s enough material to keep anyone busy for a very long time. But for me, it didn’t. The title suggests a historical novel, for the Middle Passage was the sea route used by slavers going from West Africa to the Caribbean. The book does invoke important aspects of the slave trade, life at sea in the 1830’s, and the economics and politics of 19th century America, especially in the black community. There is a Melvillean aura of authenticity about it, especially an opening scene in a New Orleans tavern that could have been taken from Moby Dick.

The title suggests a historical novel, for the Middle Passage was the sea route used by slavers going from West Africa to the Caribbean. The book does invoke important aspects of the slave trade, life at sea in the 1830’s, and the economics and politics of 19th century America, especially in the black community. There is a Melvillean aura of authenticity about it, especially an opening scene in a New Orleans tavern that could have been taken from Moby Dick. I know I am in the minority for this much-beloved book. It just didn’t work for me.

I know I am in the minority for this much-beloved book. It just didn’t work for me. The Story of Edgar Sawtelle is famous for cribbing the plot of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. The ‘king’ (Edgar’s father) is murdered by his brother Claude (Claudius) who then beds the father’s wife, Trudy (Gertrude). Edgar is the half-mad prince who accidentally kills ‘Polonius’ (a veterinarian named Papineau). Edgar later befriends a fellow named Henry (Horatio), and predictably, Edgar’s father appears as a ghost to tell Edgar that he was murdered by Claude. No Ophelia is ordered to a nunnery, but the ending is true to form, the stage littered with corpses as the curtain falls.

The Story of Edgar Sawtelle is famous for cribbing the plot of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. The ‘king’ (Edgar’s father) is murdered by his brother Claude (Claudius) who then beds the father’s wife, Trudy (Gertrude). Edgar is the half-mad prince who accidentally kills ‘Polonius’ (a veterinarian named Papineau). Edgar later befriends a fellow named Henry (Horatio), and predictably, Edgar’s father appears as a ghost to tell Edgar that he was murdered by Claude. No Ophelia is ordered to a nunnery, but the ending is true to form, the stage littered with corpses as the curtain falls.