In Wallace Stegner’s The Spectator Bird, Joe Allston, ex-New York literary agent, has retired to a quiet suburban life in Palo Alto in the 1970’s. One day he gets an innocuous postcard from an acquaintance Denmark he and his wife met on a European trip twenty years earlier. That postcard prompts him to retrieve his travel journal from the attic and in the rest of the novel, he reads it, most of it aloud to his wife, Ruth. They reminisce about the trip and the people they met, and about their long-standing marriage. The End.

In Wallace Stegner’s The Spectator Bird, Joe Allston, ex-New York literary agent, has retired to a quiet suburban life in Palo Alto in the 1970’s. One day he gets an innocuous postcard from an acquaintance Denmark he and his wife met on a European trip twenty years earlier. That postcard prompts him to retrieve his travel journal from the attic and in the rest of the novel, he reads it, most of it aloud to his wife, Ruth. They reminisce about the trip and the people they met, and about their long-standing marriage. The End.

The story line is boring as dirt and doubly unbelievable. The travel diary is written in detailed, writerly, third-person prose, not the least bit convincing. Diary-writing has its own special syntax and content, which Joe’s does not. So the diary is just a framing device to tell a long, elaborate backstory, foregrounded by a smaller, lighter story about Joe and Ruth in the present tense. Clever, but who wants to see a stage set’s scaffolding?

The second unbelievable aspect is the diary’s story, which involves the couple bumping into a Danish aristocrat manqué, renting a room from her, then visiting her old castle in the country, where they learn all sorts of dark secrets about her and her family, culminating in the revelation that Joe might actually be related to her! What are the probabilities? It’s not only an uninteresting story, it’s not the least believable.

The best part of the book is the expertly crafted writing. Every scene is written to perfection, with a purpose and a beginning, middle, and end. Every paragraph likewise. Every sentence. Anyone with experience writing cannot help but admire the craftsmanship, and that’s what it amounts to – not lyricism, not deep insight, not innovation, not provocation. The book is simply very well-written, lack of a plausible or compelling story notwithstanding. The characters are likewise cutouts and puppets. Joe is a mouthpiece for the author’s rants about life, old age, society and marriage and Ruth is his foil.

Nearly every chapter opens with extensive description of the weather and the scenery, and most close with the same. The weather! I thought at times that if I had to read one more paragraph about pewter clouds I was going to spit. It’s no wonder that young writers today are told never to do that. It’s damn boring. I’ve read good weather descriptions, such as in the last pages of Pynchon’s Inherent Vice, but Stegner’s weather is bland and unimaginative, like his scenery – literally the foliage and the quality of the dirt on the ground. That kind of writing-for-the-sake-of-writing would not pass the gatekeepers today. I’ve read good description of scenery that subtley serves as objective correlative, as in the opening scene of Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kitteredge. Stegner had no excuse and it was a slog to get through a lot of purple prose.

A couple of thematic ideas maintain some interest through the novel. The main one involves kinship, genealogy, eugenics, and Nazis. The heart of the aristocratic revelations in Denmark is that the family is riddled with incest, has been for decades, and still is. The patriarch was interested in breeding humans like cattle for “desirable” traits and conducted his own experiments within the family, the methods and outcomes of which are not detailed. We are simply supposed to be shocked at the idea of incest. It’s a cheap shot at sensationalism, not a principled inquiry. Maybe that was shocking in 1970. I wasn’t shocked.

One of the secondary, off-screen characters was supposed to have been a Nazi sympathizer, so you have the whiff of Nazi racial theories, but again, not as a developed idea and not linked to the incest theme, just a cheesy titillation. And finally, Stegner raises the weird idea that people love each other because of the relatedness of their genes. What’s wrong with incest, the narrator asks, if the people really do love each other, as long as they don’t reproduce too much. Is the best love really self-love? It’s an interesting idea, but like the others, not developed and not tied into the main story development, just thrown out there for sensationalism.

Another theme is about ageism. Joe, who is 69, rants about being excluded from society because he is old, and raves on about how the old values were better, and belittles the lifestyles of reckless, amoral youth, all the while wondering if somehow life has passed him by, because he never “did” anything. It’s not exactly an original theme, but there are a few moments of poignant sentimentality.

A final theme is about marriage – what makes a good one, how one should behave in a marriage and how one often does not, and its redeeming virtues. As a long-time married guy myself, I could recognize Joe’s thoughts and anxieties, but did not find them interesting.

Joe was just not an interesting character. For all his erudite allusions and educated sarcasm, he was a narrow –minded, burned-out curmudgeon who apparently had lived his life entirely externally, valuing physical and social achievements, a mere “spectator bird” in the garden of life. Despite his introspective voice, he apparently never developed any genuine interiority, any authentic sense of self. He has no interests, passions, or guiding vision. So if you live an empty life, focused on the outside, you end up hollow in the end. How could it be otherwise?

Joe was presented as an empty shell who seemed to realize at the end that he was an empty shell. That’s a theme worthy of a novel, but in this one, it is just a sub-theme, suggested but not deeply explored. Updike did it better in his Rabbit series.

A few years ago I tried to read Angle of Repose, supposedly Stegner’s masterpiece and couldn’t get past fifty pages, it was so boring. I tried Spectator Bird because it was short and supposedly good, having won the National Book Award in 1977. I found a few mild attractions, but this is definitely the end of my Stegner exploration.

Stegner, Wallace (1976). The Spectator Bird. New York: Quality Paperback/Doubleday/Bantam/Random. 200 pp.

I’m exhausted after selling my mother-in-law’s two-bedroom house in Los Angeles. She’s downsizing to an assisted-living place and I’ve become aware again of muscles I only vaguely remember from my youth, after packaging nearly everything and cleaning the place. It’s amazing how much stuff can be stored in a garage.

I’m exhausted after selling my mother-in-law’s two-bedroom house in Los Angeles. She’s downsizing to an assisted-living place and I’ve become aware again of muscles I only vaguely remember from my youth, after packaging nearly everything and cleaning the place. It’s amazing how much stuff can be stored in a garage. However, as a benefit, it being L.A., one always bumps against the entertainment industry bubbles of life from which we mortals are ordinarily excluded. You just can’t avoid it. For example, among the recent trips I’ve made to the city over the last few years, I accidentally met Danny DeVito and Mickey Rooney.

However, as a benefit, it being L.A., one always bumps against the entertainment industry bubbles of life from which we mortals are ordinarily excluded. You just can’t avoid it. For example, among the recent trips I’ve made to the city over the last few years, I accidentally met Danny DeVito and Mickey Rooney. On my last trip, I was supervising/helping the moving guys get my mother-in-law’s stuff to a storage locker. During a break, one of the grayed moving guys, in his fifties, I’d guess – ex-con, deeply creased face, fully tattooed, heavily sweating, revealed that he’d moved Ben Affleck once and reported that he was a good actor, but – and here he lowered his voice in confidentiality – his tattoos were lame and had too much color. Wow, who knew that was a criterion for social judgment? Still, it was titillating to be within so few degrees of separation of the immortals.

On my last trip, I was supervising/helping the moving guys get my mother-in-law’s stuff to a storage locker. During a break, one of the grayed moving guys, in his fifties, I’d guess – ex-con, deeply creased face, fully tattooed, heavily sweating, revealed that he’d moved Ben Affleck once and reported that he was a good actor, but – and here he lowered his voice in confidentiality – his tattoos were lame and had too much color. Wow, who knew that was a criterion for social judgment? Still, it was titillating to be within so few degrees of separation of the immortals.

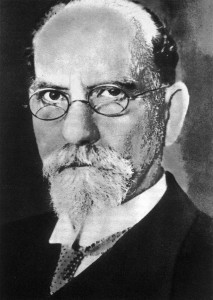

I read philosophical work by Edmund Husserl, the inventor of phenomenology, all translated into English from German, most of it impenetrable. The more I studied, the more I realized phenomenology was a useful method but fundamentally flawed by unexamined assumptions, including essentialism, elementalism, epistemological dualism, scientism, and commitment to sense-data. These limitations prevent it from being a fully successful methodology for examining the mind. It was, and still is, useful in analysis of relatively well-defined problems.

I read philosophical work by Edmund Husserl, the inventor of phenomenology, all translated into English from German, most of it impenetrable. The more I studied, the more I realized phenomenology was a useful method but fundamentally flawed by unexamined assumptions, including essentialism, elementalism, epistemological dualism, scientism, and commitment to sense-data. These limitations prevent it from being a fully successful methodology for examining the mind. It was, and still is, useful in analysis of relatively well-defined problems. The conference leaders and attendees are intimidating academics and philosophical clergy, most from the Bay Area but some from Bulgaria, of all places, affiliates of Eastern Orthodox Christianity and a conference co-sponsor in Sofia. These people seriously know what they’re talking about, whereas I just have some ideas I developed myself. So I’ll probably get ripped apart at the conference, but I don’t mind. It’s an experience.

The conference leaders and attendees are intimidating academics and philosophical clergy, most from the Bay Area but some from Bulgaria, of all places, affiliates of Eastern Orthodox Christianity and a conference co-sponsor in Sofia. These people seriously know what they’re talking about, whereas I just have some ideas I developed myself. So I’ll probably get ripped apart at the conference, but I don’t mind. It’s an experience. This is my second Murakami experience and it was a good one. I read Wind-Up Bird Chronicle and found it relentlessly inventive but not much else. Hard-Boiled, however, has plenty of chewy meat beneath the author’s famous razzle-dazzle style.

This is my second Murakami experience and it was a good one. I read Wind-Up Bird Chronicle and found it relentlessly inventive but not much else. Hard-Boiled, however, has plenty of chewy meat beneath the author’s famous razzle-dazzle style. To the Lighthouse is a novelistic exploration of individual consciousness and of relationships in the interwar period in Britain. Woolf uses a stream of consciousness technique to tell us what characters are thinking and feeling. The narrator promiscuously jumps from one head to another, so much so that a reader can lose track of whose POV is being expressed. It’s easy to see why such head-hopping is verboten for writers today.

To the Lighthouse is a novelistic exploration of individual consciousness and of relationships in the interwar period in Britain. Woolf uses a stream of consciousness technique to tell us what characters are thinking and feeling. The narrator promiscuously jumps from one head to another, so much so that a reader can lose track of whose POV is being expressed. It’s easy to see why such head-hopping is verboten for writers today. My new novel is developing slowly. I have 7,000 words since I started writing on August 1. That’s 500 words a day, a couple of pages, respectable, but I haven’t been feeling momentum.

My new novel is developing slowly. I have 7,000 words since I started writing on August 1. That’s 500 words a day, a couple of pages, respectable, but I haven’t been feeling momentum. Can you infer anything about a writer’s biography from what he or she has written? As a writer of fiction, I have to say, yes you can make valid inferences at a high level of abstraction, but no, you can’t infer much about specific experience. I write literary fiction, mysteries, and science fiction even though I’ve never shot anyone, met a space alien or lived in the nineteenth century. Non-writers of fiction may underestimate the power of imagination. Writers of fiction make stuff up and then convince you it could be true. That’s the job.

Can you infer anything about a writer’s biography from what he or she has written? As a writer of fiction, I have to say, yes you can make valid inferences at a high level of abstraction, but no, you can’t infer much about specific experience. I write literary fiction, mysteries, and science fiction even though I’ve never shot anyone, met a space alien or lived in the nineteenth century. Non-writers of fiction may underestimate the power of imagination. Writers of fiction make stuff up and then convince you it could be true. That’s the job. Setting a novel in a historical period is much more difficult than I had anticipated because of the endless research. I was writing a scene that mentioned a pipe-cleaner when I stopped short: Wait! Did they have pipe cleaners in 1900 in America? Yes. Would my character be writing a letter with a quill pen? No. Steel-tip nibs in hard rubber holders were commonplace. Fountain pens existed but were expensive and unreliable. What did people wear? Shirts and blouses made at home from mail-order fabric (Sears). Overalls and no underwear in the summer for men. Brassieres for the ladies? No. The brassiere was invented in the late 1800s but rural women in America didn’t see what problem it solved. All clothes were fastened with buttons. The zipper hadn’t been invented. Elastic was rare.

Setting a novel in a historical period is much more difficult than I had anticipated because of the endless research. I was writing a scene that mentioned a pipe-cleaner when I stopped short: Wait! Did they have pipe cleaners in 1900 in America? Yes. Would my character be writing a letter with a quill pen? No. Steel-tip nibs in hard rubber holders were commonplace. Fountain pens existed but were expensive and unreliable. What did people wear? Shirts and blouses made at home from mail-order fabric (Sears). Overalls and no underwear in the summer for men. Brassieres for the ladies? No. The brassiere was invented in the late 1800s but rural women in America didn’t see what problem it solved. All clothes were fastened with buttons. The zipper hadn’t been invented. Elastic was rare. This mid-century, noirish psychological thriller has something in common with The Maltese Falcon. Both stories feature a classic “MacGuffin,” an arbitrary object of desire that all parties seek, pursuit of which drives the action of the story. The tale also has a Lolita-like element in that the bad guy cynically marries a widowed woman just to get close to her kids who seem to know where the MacGuffin is.

This mid-century, noirish psychological thriller has something in common with The Maltese Falcon. Both stories feature a classic “MacGuffin,” an arbitrary object of desire that all parties seek, pursuit of which drives the action of the story. The tale also has a Lolita-like element in that the bad guy cynically marries a widowed woman just to get close to her kids who seem to know where the MacGuffin is. I watched Hillary Clinton closely as she gave her acceptance speech at the Democratic Convention on Thursday night. I was hoping for something spectacular. I hoped in vain.

I watched Hillary Clinton closely as she gave her acceptance speech at the Democratic Convention on Thursday night. I was hoping for something spectacular. I hoped in vain.