I spent a week in New York City attending a conference on how to pitch a novel to an agent or editor. Selling fiction is the least appealing part of the writing adventure. I write because I enjoy the thrill of creative work and artistic expression, and because I imagine I can delight others with a tale. Selling a manuscript is not on the list of attractions, but it’s necessary if one hopes to find an audience. It was time, past time, to try and find a serious publisher for my work. Thus the how-to conference.

I spent a week in New York City attending a conference on how to pitch a novel to an agent or editor. Selling fiction is the least appealing part of the writing adventure. I write because I enjoy the thrill of creative work and artistic expression, and because I imagine I can delight others with a tale. Selling a manuscript is not on the list of attractions, but it’s necessary if one hopes to find an audience. It was time, past time, to try and find a serious publisher for my work. Thus the how-to conference.

The pre-conference “homework” was explicit about describing the novel being pitched and it wasn’t easy. What exactly is my main character’s secondary conflict? How should I describe my antagonist’s endgame? It was a difficult exercise in seeing the manuscript from the other side of the table. I did the homework, prepared my pitch and went to the Big Apple to test it. The result was a revelatory roller-coaster.

The meetings were held in a nondescript office building in Manhattan. Two floors were dedicated to performing arts and were thronged with people auditioning for parts or using the many practice rooms. Up front, near the elevators, a bulletin board on an easel listed the auditions for that morning. The labyrinthine hallways were lined with wooden benches, folding chairs, park benches, and plastic patio chairs pressed against thickly-painted wooden wainscoting. All that seating was filled with people, mostly young, studying scripts and scores, reading, and talking nervously.

The meetings were held in a nondescript office building in Manhattan. Two floors were dedicated to performing arts and were thronged with people auditioning for parts or using the many practice rooms. Up front, near the elevators, a bulletin board on an easel listed the auditions for that morning. The labyrinthine hallways were lined with wooden benches, folding chairs, park benches, and plastic patio chairs pressed against thickly-painted wooden wainscoting. All that seating was filled with people, mostly young, studying scripts and scores, reading, and talking nervously.

As I navigated the corridors, a changing spectrum of music and voices came from behind closed doors – people practicing scales, singing show tunes or operatic arias. Pianos plinked and choirs harmonized. Waves of cacophony drew me deeper.

As I navigated the corridors, a changing spectrum of music and voices came from behind closed doors – people practicing scales, singing show tunes or operatic arias. Pianos plinked and choirs harmonized. Waves of cacophony drew me deeper.

I found myself blocked by young women in leotards lying on their backs, stretching their legs in the air. I knew it was not the correct zone. Writers don’t wear ballet slippers. An older woman with short gray hair, holding a clipboard, popped out of a doorway and barked, “Zellner?” Somebody, presumably Zellner, got up from a bench and went in.

I found my way to a corridor lined with what looked like writers. Most were hunched over laptops balanced on their knees. I sat and verified it was the place. Before long the door to the practice/audition room opened and three dozen writers went inside. The room was large, cold, and bare, covered with well-scuffed pale hardwood, walled on one end with floor-to-ceiling mirror, and on two sides with wood-framed windows with dirty glass overlooking 8th Avenue and 37th Streets. A black upright piano guarded the other wall. We sat in folding chairs facing a folding table.

I found my way to a corridor lined with what looked like writers. Most were hunched over laptops balanced on their knees. I sat and verified it was the place. Before long the door to the practice/audition room opened and three dozen writers went inside. The room was large, cold, and bare, covered with well-scuffed pale hardwood, walled on one end with floor-to-ceiling mirror, and on two sides with wood-framed windows with dirty glass overlooking 8th Avenue and 37th Streets. A black upright piano guarded the other wall. We sat in folding chairs facing a folding table.

The conference conveners called out names and assigned us to groups presumably based on our homework submissions, and we dispersed to other, similar rooms for our first meeting. In my meeting the leader introduced herself then we went “around the room” with people giving names and describing their project. That’s what we call a novel-in-progress, a “project,” because no novel is ever “completed.” You just revise it over and over until you give up in exhaustion and that counts as “done.” For the time being.

I was in the “literary fiction” group. People in my group, I learned, were MFAs, college writing instructors, and screenwriters. Their projects focused on family infighting, questions of ethnic identity, kinship relations, and family secrets uncovered. My heart sank. These projects sounded deadly. When it was my turn, I was abashed.

“Well, my story does feature a space-alien, so I guess that makes it sci-fi.”

The room went silent, as if I had just laid a turd on the floor. The instructor stared at me.

“You have an alien?”

“Yup.”

“Oh, dear. Are you supposed to be in this group?”

“This is where I was assigned.”

“No, no no. Let me check.”

The instructor leapt to her feet and bolted from the room. She returned in a minute told me I was supposed to be in Studio “P” for genre. Okay. So I gathered my things. As I left, one of the students said,

The instructor leapt to her feet and bolted from the room. She returned in a minute told me I was supposed to be in Studio “P” for genre. Okay. So I gathered my things. As I left, one of the students said,

“I liked that alien. The one who looks like a green beach ball? That sounds really interesting.” She had read it on the online site where we posted the homework.

I smiled and rushed over to Studio P, thinking, I can’t believe I’ve just been kicked out of literary fiction! What does that mean?

I found the new group in progress, grabbed and unfolded a chair at the end of the semicircle, and the leader suddenly finished his introductory spiel and turned to me and said, “Okay, let’s start on this end. Let’s hear your pitch.”

I don’t have my computer started, don’t even have my notebook out of my brief case. Everyone stares at me. I start talking. I do know my material, but I have nothing to read from. I’m winging it.

At the end of my pitch, the leader looks at me and says,

“Humor doesn’t sell. You got anything else?”

He was only half-kidding. He was a wiseguy, though well-meaning, I eventually learned. Flustered, I babbled for a moment, then let it go. Next victim.

Other pitches didn’t go as well as mine. One, the leader interrupted mid-sentence.

“Did you say a school for wizards?”

“Yes.”

“Get out.” He pointed to the door.

The student flushed with color but hung his head and didn’t leave.

“And if anybody has vampires or zombies, go with him now,” the instructor added.

“Steam punk?” one student asked.

“Out.”

Brutal is hardly the word for it. The writers in the room were paralyzed so the instructor let up on his tough-guy persona and started to explain why the pitches so far were no good and what it would take for a successful pitch. Nobody actually had to leave.

The interviews then continued with everybody having an equal chance to be abused and ravaged by the workshop leader. He knew the NY publishing market and purported to know what sells and what doesn’t and the exact reasons why each pitch stank. It was educational.

As I staggered out of the audition room for the lunch break, the hallways were still lined with hopefuls waiting to be called, the air still filled with do-me-so-do’s. I had to weave around clusters of tiny girls in pink tights and white tutus herded by anxious mothers. I saw at the front there was an audition for a production of “Annie.”

As I staggered out of the audition room for the lunch break, the hallways were still lined with hopefuls waiting to be called, the air still filled with do-me-so-do’s. I had to weave around clusters of tiny girls in pink tights and white tutus herded by anxious mothers. I saw at the front there was an audition for a production of “Annie.”

Thank God I’m not in show business, I thought. Then: Wait! I am in show business! What I’m doing here has nothing to do with writing and everything to do with performance. Oh, God.

To be continued…

To be continued…

I like Chris Hayes. I like his news/talk show on MSNBC, “All In.” I’ve enjoyed him since he started out in a 5 am TV time slot. He’s the smartest pundit on TV.

I like Chris Hayes. I like his news/talk show on MSNBC, “All In.” I’ve enjoyed him since he started out in a 5 am TV time slot. He’s the smartest pundit on TV. This short haunted house tale is celebrated as a classic of the genre, a top-seller since its publication in 1959, although I don’t normally read haunted house stories so I can’t judge that. Nevertheless, it accomplishes the goal of presenting a haunted house by ticking all the right boxes, and with the added virtue that the “ghosts” themselves never appear onstage. In keeping with modern realism, ambiguity is built into the narrative, so you’re never sure whether the characters are haunted by real, “out-there” ghosts of the dead, or by their own, in-the-head fears, anxieties, and neuroses. They don’t know, and either do we, the readers. Either way, the fear is palpable to the characters.

This short haunted house tale is celebrated as a classic of the genre, a top-seller since its publication in 1959, although I don’t normally read haunted house stories so I can’t judge that. Nevertheless, it accomplishes the goal of presenting a haunted house by ticking all the right boxes, and with the added virtue that the “ghosts” themselves never appear onstage. In keeping with modern realism, ambiguity is built into the narrative, so you’re never sure whether the characters are haunted by real, “out-there” ghosts of the dead, or by their own, in-the-head fears, anxieties, and neuroses. They don’t know, and either do we, the readers. Either way, the fear is palpable to the characters. I traded in my 12-year-old Scion xB for a new car. That boxy look was all the rage back when Hummers and Elements, and other functional-looking cargo vehicles were in vogue. The Scion was a fun car to drive despite its meager 100 horsepower, got good mileage around town (30+), had great visibility for the driver, with a nice high vantage point, and it really did pack a lot of cargo space into a small volume. And it was cheap – cheap to buy ($14K in decade-old dollars) and cheap to run (regular gas, Toyota engine that lasted forever with almost no maintenance). It was so cheap that I could afford to put 18” alloy wheels with low-profile tires on it, and it looked very fine, indeed, a strutter.

I traded in my 12-year-old Scion xB for a new car. That boxy look was all the rage back when Hummers and Elements, and other functional-looking cargo vehicles were in vogue. The Scion was a fun car to drive despite its meager 100 horsepower, got good mileage around town (30+), had great visibility for the driver, with a nice high vantage point, and it really did pack a lot of cargo space into a small volume. And it was cheap – cheap to buy ($14K in decade-old dollars) and cheap to run (regular gas, Toyota engine that lasted forever with almost no maintenance). It was so cheap that I could afford to put 18” alloy wheels with low-profile tires on it, and it looked very fine, indeed, a strutter. The decision to sell came after rats got into it and ate the carpets and the wiring. Disgusting. These are small pack-rats that live in the desert, not big, black river rats that the word “rat” probably conjures to mind for most people. Pack-rats are actually kind of cute, but they’re still rats and not welcome.

The decision to sell came after rats got into it and ate the carpets and the wiring. Disgusting. These are small pack-rats that live in the desert, not big, black river rats that the word “rat” probably conjures to mind for most people. Pack-rats are actually kind of cute, but they’re still rats and not welcome. I cleaned out the nest and all the treasures distributed under the seats and throughout the cabin, no easy task. I never saw the little homeowners themselves, thank goodness. They’re nocturnal, I believe. I got the wiring repaired. The shop said rat damage was very common and that I had gotten off lightly. Fortunately I’d caught them before they’d done serious harm and engine still worked fine.

I cleaned out the nest and all the treasures distributed under the seats and throughout the cabin, no easy task. I never saw the little homeowners themselves, thank goodness. They’re nocturnal, I believe. I got the wiring repaired. The shop said rat damage was very common and that I had gotten off lightly. Fortunately I’d caught them before they’d done serious harm and engine still worked fine.

That’s the idea, anyway. In practice, it’s not a reasonable way to drive. In fifth gear I might be hitting 44 mpg according to the read-out, but I have no reserve acceleration. In city driving, you need to be ready to make moves. You can’t coast through town. So I run it in fourth, or even third because I see a hill up ahead or a city bus I’ll have to go around, and my mpg is sub-optimal because I’m driving in too low a gear.

That’s the idea, anyway. In practice, it’s not a reasonable way to drive. In fifth gear I might be hitting 44 mpg according to the read-out, but I have no reserve acceleration. In city driving, you need to be ready to make moves. You can’t coast through town. So I run it in fourth, or even third because I see a hill up ahead or a city bus I’ll have to go around, and my mpg is sub-optimal because I’m driving in too low a gear. It won’t be long, possibly in my lifetime, before the whole idea of an individually piloted motor vehicle will seem absurd. The idea that millions of hairless monkeys are each qualified to safely guide several tons of glass and steel at high speed, separated from each other only by paint on the roadways, is ridiculous. Future generations will look back on this era and say, “Really?” But for now, the age of cars and petroleum is just beginning to come to a close and while it persists, this monkey wants to enjoy piloting his death-trap along the road.

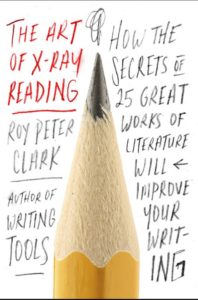

It won’t be long, possibly in my lifetime, before the whole idea of an individually piloted motor vehicle will seem absurd. The idea that millions of hairless monkeys are each qualified to safely guide several tons of glass and steel at high speed, separated from each other only by paint on the roadways, is ridiculous. Future generations will look back on this era and say, “Really?” But for now, the age of cars and petroleum is just beginning to come to a close and while it persists, this monkey wants to enjoy piloting his death-trap along the road. This is a great book to help someone who wants to upgrade their reading fare from genre to literary fiction. It teaches you how to pay attention to meta-textual details such as themes, symbols, voice, diction, and story structure. Attention to such details will surely enhance anyone’s reading enjoyment.

This is a great book to help someone who wants to upgrade their reading fare from genre to literary fiction. It teaches you how to pay attention to meta-textual details such as themes, symbols, voice, diction, and story structure. Attention to such details will surely enhance anyone’s reading enjoyment. I just finished re-reading Art &Lies by Jeanette Winterson and was again elevated by her lyrical language, though unlike my first awe-struck read, about four years ago, this time I noted more over-writing and self-indulgent wordplay – not that I could ever do any better with the language than she.

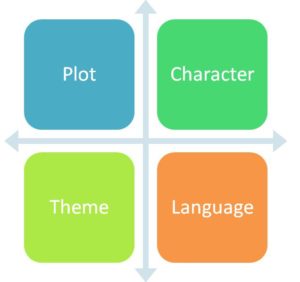

I just finished re-reading Art &Lies by Jeanette Winterson and was again elevated by her lyrical language, though unlike my first awe-struck read, about four years ago, this time I noted more over-writing and self-indulgent wordplay – not that I could ever do any better with the language than she. The most successful fictional stories combine strong characters with strong plot. The classic example is Oedipus Rex by Sophocles. In such cases, plot is character, as they say. The events of the story are driven by the character’s intentionality, and in turn, the character’s reactions are provoked by story events in equal measure. Other examples include The Third Man, Olive Kitteridge, Winter’s Bone, Sanctuary.

The most successful fictional stories combine strong characters with strong plot. The classic example is Oedipus Rex by Sophocles. In such cases, plot is character, as they say. The events of the story are driven by the character’s intentionality, and in turn, the character’s reactions are provoked by story events in equal measure. Other examples include The Third Man, Olive Kitteridge, Winter’s Bone, Sanctuary. I was a fan of le Carré for decades. I read every one of his novels, from “Call for the Dead” to “A Small Town in Germany” and on forward. He was my favorite author and I’d often buy the full-price hardback when a new novel came out, rather than wait for the paperback.

I was a fan of le Carré for decades. I read every one of his novels, from “Call for the Dead” to “A Small Town in Germany” and on forward. He was my favorite author and I’d often buy the full-price hardback when a new novel came out, rather than wait for the paperback. I am grinding out sentences on my ninth novel as if it were school homework. I’ve been working on Chapter Six since the middle of September, six weeks, and I estimate I have another two weeks to go on it. My previous novels were drafted at warp speed, often a thousand words a day, for weeks on end. Those days are gone.

I am grinding out sentences on my ninth novel as if it were school homework. I’ve been working on Chapter Six since the middle of September, six weeks, and I estimate I have another two weeks to go on it. My previous novels were drafted at warp speed, often a thousand words a day, for weeks on end. Those days are gone. It’s really difficult to design each scene’s purpose and subtle movements without the cheap thrill of a wide-screen, technicolor, kinetic vision of what’s supposed to be. I’m working an old-time pipe organ in a cavernous church, pulling and pushing stops, adjusting registers, listening to the sound, but confined to the console in front of me. Everything must be manufactured anew as I call for each new pitch and timbre. And I’m molting as I do it.

It’s really difficult to design each scene’s purpose and subtle movements without the cheap thrill of a wide-screen, technicolor, kinetic vision of what’s supposed to be. I’m working an old-time pipe organ in a cavernous church, pulling and pushing stops, adjusting registers, listening to the sound, but confined to the console in front of me. Everything must be manufactured anew as I call for each new pitch and timbre. And I’m molting as I do it. I am sorely tempted to take a break from this project and start another I have in mind involving a televangelist committing financial fraud. But that would be falling off the wagon, wouldn’t it? I will try to stay the course until all my feathers have fallen out.

I am sorely tempted to take a break from this project and start another I have in mind involving a televangelist committing financial fraud. But that would be falling off the wagon, wouldn’t it? I will try to stay the course until all my feathers have fallen out. The Orphan Master’s Son is a grim book with a high gross-out factor, so if you don’t tolerate torture and gore well, it wouldn’t be for you. But if you enjoy the creativity of trying to depict sheer horror, it’s great.

The Orphan Master’s Son is a grim book with a high gross-out factor, so if you don’t tolerate torture and gore well, it wouldn’t be for you. But if you enjoy the creativity of trying to depict sheer horror, it’s great. I recently pulled into my usual hotel in Yuma, AZ and the place was jammed. I had trouble finding a parking spot. Good thing I had a reservation because the hotel was completely full. It was unusual. Yuma, Arizona?

I recently pulled into my usual hotel in Yuma, AZ and the place was jammed. I had trouble finding a parking spot. Good thing I had a reservation because the hotel was completely full. It was unusual. Yuma, Arizona? men in heavy boots, green or brown camouflage, big knives sheathed on their belts, backpacks rather than suitcases, some with leashed dogs – and these were largish dogs, not lap dogs. I didn’t see any women or children.

men in heavy boots, green or brown camouflage, big knives sheathed on their belts, backpacks rather than suitcases, some with leashed dogs – and these were largish dogs, not lap dogs. I didn’t see any women or children. Before I left in the morning, out of curiosity I went around back of the hotel to the “cleaning station.” It was only eight in the morning but a group of four men were apparently the last of the morning hunters. They go out before dawn, I learned. They were milling around a pair of folding tables covered in feathers, blood, knives, and plastic bags. They hosed off sections of the table as they worked. Dogs sat and lay nearby huge pickup trucks with elevated beds. Shotguns rested vertically near the tables and near the trucks. There were many more guns than men, but the men were friendly and eager to answer my questions as they worked.

Before I left in the morning, out of curiosity I went around back of the hotel to the “cleaning station.” It was only eight in the morning but a group of four men were apparently the last of the morning hunters. They go out before dawn, I learned. They were milling around a pair of folding tables covered in feathers, blood, knives, and plastic bags. They hosed off sections of the table as they worked. Dogs sat and lay nearby huge pickup trucks with elevated beds. Shotguns rested vertically near the tables and near the trucks. There were many more guns than men, but the men were friendly and eager to answer my questions as they worked. As I drove through the barren desert east of Yuma I thought about the dove hunt. I had accidentally stepped into a completely alien world, as if I had been abducted to an extraterrestrial space ship. It wasn’t merely that I have never hunted, especially not pigeons. There are a lot of things I’ve never done. And my uncomfortable feeling wasn’t about cruelty to animals, which I abhor, because I accept hunting as a legitimate sport in the context of conservation. I wouldn’t support head-hunting just for trophies, but hunters are a legitimate part of the ecology in controlling populations of deer, wolves, and other animals in the west. Part of nature.

As I drove through the barren desert east of Yuma I thought about the dove hunt. I had accidentally stepped into a completely alien world, as if I had been abducted to an extraterrestrial space ship. It wasn’t merely that I have never hunted, especially not pigeons. There are a lot of things I’ve never done. And my uncomfortable feeling wasn’t about cruelty to animals, which I abhor, because I accept hunting as a legitimate sport in the context of conservation. I wouldn’t support head-hunting just for trophies, but hunters are a legitimate part of the ecology in controlling populations of deer, wolves, and other animals in the west. Part of nature. As the hypnotic miles slipped past, I decided it’s really not about survivalism at bottom. It’s about individualism. The myth, especially strong in the west, especially among the under-educated is that we are monads, each person a self-contained, self-sufficient individual and we all must make our own way in life. That was the fantasy these men were living.

As the hypnotic miles slipped past, I decided it’s really not about survivalism at bottom. It’s about individualism. The myth, especially strong in the west, especially among the under-educated is that we are monads, each person a self-contained, self-sufficient individual and we all must make our own way in life. That was the fantasy these men were living.