This is the latest post in the series on my writing process during the long struggle to create Chocotle, which wants to be a novel. It now has 23,000 words, which is 25% to 33% of a modest novel. I like to finish around 300 pages, which is about 75,000 words. I assume at least 10% of it will be cut in editing, so I should be aiming at 85,000 words.

This is the latest post in the series on my writing process during the long struggle to create Chocotle, which wants to be a novel. It now has 23,000 words, which is 25% to 33% of a modest novel. I like to finish around 300 pages, which is about 75,000 words. I assume at least 10% of it will be cut in editing, so I should be aiming at 85,000 words.

Actually, I don’t aim at any word count. I just write. I monitor word count so I can see progress, which is rewarding in itself, but mainly to get a sense of the pace. I conceptualize the story in terms of Beginning, Middle, and End, so if I’m at 50,000 words and still trying to establish the status quo, I know I am way off course. I like the beginning and end to be 25,000, and the middle about 50,000. In the Beginning, I set the status quo then smash it. I feel that I am getting near the end of the Beginning, so my current word count feels about right.

What I’ve got so far, at least in my self-deluded mind, is that Scott’s status quo as a happy husband and father, and successful and affluent advertising man, has already started to seriously deteriorate. By the end of Chapter 6, he had “turned like a sunflower facing a different sun,” and he couldn’t make himself go back to work after his forced 2 weeks of vacation. I’m sure we all know the feeling, but Scott really didn’t go back and he’s in serious doo-doo.

Chapter 7 will send him over the edge, irretrievably into the abyss. That’s the short goal statement for that chapter. Chapter 8, the end of the Beginning, will have him utterly hit bottom, everything gone, nothing left. That’s as far as I can see right now.

As I started to set up Chapter 7, using the template I described in an earlier post, I realized I need a name and an identity for someone I’ve been calling “Mr X,” the fellow who Allie has an affair with. That is a much more difficult sub-project than it seems.

The names of characters help the reader connect to them. People’s names are merely identifiers, not even unique ones, virtually arbitrary, not self-chosen, and they mean nothing. Whether your name is Smith or Pendergast has no bearing on what kind of a person you are. Yet in readers’ minds, it does.

Names have sounds, and they have connotations. To use characters’ names to advantage, they should be chosen carefully. Actor John Wayne’s real name was Marion Morrison. That would never do for a western tough-guy hero. But why not? What’s wrong with Marion Morrison? It’s a real name for a real person, the very actor we came to love on screen. I can’t say exactly what’s wrong with the name, but few people would disagree that “John Wayne” worked better than “Marion Morrison” ever could have.

Charles Dickens had a great time with character names. He was quite aware of their connotative associations, and he liked to play with that. In Bleak House, for example, the venal lawyers who bill clients so mercilessly that there is finally nothing left of their claim, are called Jarndyce and Jarndyce. The similarity to the word “jaundice” is not accidental. The white, old and pinched, aristocratic, and desiccated lord and lady of the manor are the Dedlocks. The woman who talks incessantly about her former husbands is Mrs. Badger. The small, misshapen fellow who annoys the main character is Mr. Guppy. A frivolous and obnoxious woman is Mrs. Pardiggle.

I use more traditional names, but still with an ear to connotation. Scott Garrison is so named because a garrison is a military fort or barracks and in this story, Scott will spend quite a bit of time hunkered down. He’s named Scott because despite his profligate ways in the beginning, he’s fundamentally frugal, and people associate frugality with the Scots. So it’s not a bad name for him.

I keep several files of names in the computer. I collect them from actual lists of names I find, such as contributors to the local theater, from the newspapers, and of course from the internet. There are millions of names on the internet. Just enter “baby names” into a search engine and see what you get. The problem is not finding names; it’s choosing. How is that done? Intuition, mainly. Here are some examples of how I chose character names from my lists.

When I was looking for Scott Garrison, I wanted a male, Caucasian, American, just under 40, an ad man. I selected a few first names (left two columns) and some last names (right two columns) and put them in a grid. These names were selected intuitively, for their sound and not-quite-conscious connotations.

| Martin |

Craig |

|

Mayfield |

Moss |

| Grant |

Winston |

|

Tate |

Cross |

| Mason |

Truman |

|

Baxter |

Garrison |

| Carter |

Alec |

|

Holder |

Hatcher |

| Kevin |

Paul |

|

Wilder |

Washburn |

| Travis |

Edward |

|

Goodrich |

Hemphill |

| Winslow |

Mark |

|

Brothers |

Parsons |

| Scott |

Curtis |

|

Biggs |

Fellows |

Then I tried combining first and last names to see if any were memorable, unique, believable, and had a strong, positive, likeable main character sort of feel, whatever that is. I also looked for slightly lower frequency, when appropriate – not so many Tom, Dick and Harrys. Then I went through and highlighted the most promising ones.

Martin Mayfield; Craig Garrison; Grant Baxter; Grant Whittaker; Truman Cross; Carter Mayfield; Alec Goodrich; Alec Fellows; Kevin Cross; Kevin Fellows; Paul Biggs, Paul Baxter; Paul Holder; Paul Tate; Travis Biggs; Travis Moss; Edward Mayfield; Edward Parsons; Edward Fellows; Mason Brothers; Winslow Hatcher; Winston Fellows; Alec Winston; Winslow Carter; Kevin Carter; Paul Finder; Paul Hatcher. Chris Cross; Walter Washburn; Martin Parsons; Mark Biggs; Grant Wilder; Mark Wilder; Scott Mayfield; Scott Baxter; Scott Parsons; scott Fellows; Mason Webb; Martin Webb; Steve Ralston, Karl Block, Gordon Gallup, Ken “King” Cole, Jeremy Barksdale, Matt Hightower, Alexander Cook, Sean Masterson,

John Curry, John Packard, John Truax, John Click, John Coffee,

Ted Packard, Ted Truax, Ted Click, Ted Cross, Chris Cross

Scott Baxter, Scott Lovett, Scott Hightower, Scott Garrison

As I picked through the list of combinations, I seriously considered “John” and “Ted,” but finally focused on “Scott” as my preferred first name, fairly soon, and arrived at “Garrison.” I also used Ken “King” Cole, in a different project because I just liked that one. I like the possibilities for good nicknames, as in, “His name was Johnny Webb but everybody called him Spider.” I collect those, but rarely use them. Maybe they’re too silly.

Charlie Charles (Chuck-chuck), Stan Stanley, John Johnson, Will Williams, Meya Meyapann, Robert Roberts, Richard Dick (Dickey Dick);

I also like names that have musical, alliterative, or just interesting sounds, but I also rarely use those, for some reason.

Becky Baker, Ellen Oatley, Dee Dee Zee, Ann McLang, Vito Valdivia, Brick Bracken.

And I collect real names that I like, but since these are real, living people whose names have been published for some reason, I’ve always been afraid to use them:

Jack Biggerstaff, Coral Reefe, Peter Elbow, Buganoni Spezzia, Quinton McKracken, Krystal Fogg, Jimmy Wallet, Leonard Lion (middle name should be Theodore), Mary Sheepshank, Timothy Salthouse, Michael Starbird, Brick Johnstone

Here’s another example of selecting a name. I needed a sneaky, somewhat dim bad guy; white, a real lowlife. I put potential first names on the left and last names on the right, then tried promising combinations, as before.

| Willie |

Trader, Dealer, Monger |

| Andy |

Proctor, Proxmire |

| Roy |

Packer, Packman |

| Randy |

Yeoman |

| Bobby |

Lander, Swain, Tiller |

| Earl |

Feeney, Nunn, Lyman |

| Vern |

McGee, Merchant |

| Tony |

Gardner |

Randy Swain, Earl Feeney, Roy Lyman, Bobby Lyman, Bobby Gardner, Willie Gardner, Roy Nunn, John Lyman, John Lander

Notice that, for me, lowlife first names tend to end in “y,” as if names for children or dogs, because these people lack dignity. I liked “Lyman” for the last name, because it connotes a liar. Other last names suggest common laborers, such as gardner, yeoman, monger, and merchant. (No offense to anyone who happens to have one of these fine names! I’m talking about irrational, barely conscious associations to the names themselves, before there is a person attached.) I ended up going with Randy Swain in this example. “Swain” is an archaic word for a young lover, which most readers wouldn’t know, but it adds an extra dimension.

One final example. I needed the name of a tough-guy, vigilante cop; a name that would be just a little too obvious, almost ironic because he was a pulp-fiction character. Here’s how I selected:

| Danny |

Vince |

Burns |

Striker |

| Sal |

Roman |

Walker |

Bigatti |

| Harry |

Ben |

Hammer |

Barefoot |

| Jimmy |

Tony |

Galambos |

Wells |

| Clint |

Clay |

Vandello |

Block |

Danny Burns, Vince Hammer, Tony Bigatti, Ben Walker, Roman Striker, Clay Wells, Kurt Hammer, Jimmy Striker, Flint Striker, Sam Spear, Vince Armstrong, Clint Armstrong, Clay Armstrong, Sam Striker, Clay Savage.

I finally went with “Clint Savage” for my cartoony cop.

I’ve gone through the same kind of procedure for all my characters. And sometimes even after choosing, I decide I don’t like the name and I have to choose another then go through the manuscript with a global search and replace. The change is shocking after you get to know a character by a certain name.

I also try to avoid too-obvious racial and ethnic stereotypes, although if you want the name to suggest characteristics to the reader, you can’t be too shy. I’ve searched for, and found “the most black-sounding first names” and “the most white-sounding first names.” I have separate lists for black characters, Native Americans, Swedes, Greeks, Russians, and many other categories.

I usually Google the name I’ve selected, just to see if I need to avoid a real person’s name and a potential libel suit. Just about every name that can be synthesized is actually owned by someone in the world, but I don’t want the real person to have similar characteristics to my character, such as by being in the same line of work or even living in the same city.

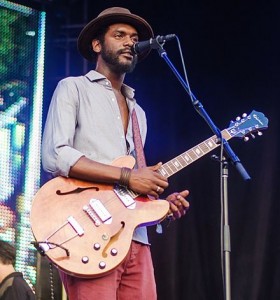

Choosing a character’s name is a difficult process that I do not enjoy. It can take several hours to come up with one, and the result may end up being unsatisfactory after a few days. But it has to be done. Right now, I need a name for “Mr. X,” Allie’s paramour. I’m thinking he’s going to be black, 40 to 45, an urban professional, possibly a professor, affluent, well-educated, and married, so a bit of a sleazeball (like her). He may not actually appear on stage, I’m not sure yet. It will take some time.

Some useful sources of names include:

http://www.behindthename.com/glossary/view/name_element What names mean.

http://names.mongabay.com/most_common_surnames.htm Surnames by frequency, can be sorted by year to see historical trends.

Ethnic Name Generators

http://www.starmanseries.com/toolkit/names.html

http://www.atlantagamer.org/iGM/RandomNames/index.php

Myers-Briggs Character Generator

http://character.namegeneratorfun.com/