I recently decided to print up some physical copies of my first ebook, Hunter and Hunted, which has been for sale at Smashwords, Kindle, and Nook for two years. At 51,000 words, it was the first novel-length piece I wrote, an international thriller involving art fraud. It sells the occasional copy, heaven only knows to whom or why, perhaps 6 copies a year. Its problem is what the industry calls “discoverability,” or lack of same. Nobody knows of this book’s existence, and among people who do happen to find it, there is no reason on this earth why they should buy it. Such is the fate of self-published ebooks.

I recently decided to print up some physical copies of my first ebook, Hunter and Hunted, which has been for sale at Smashwords, Kindle, and Nook for two years. At 51,000 words, it was the first novel-length piece I wrote, an international thriller involving art fraud. It sells the occasional copy, heaven only knows to whom or why, perhaps 6 copies a year. Its problem is what the industry calls “discoverability,” or lack of same. Nobody knows of this book’s existence, and among people who do happen to find it, there is no reason on this earth why they should buy it. Such is the fate of self-published ebooks.

Still, on reading it again, I realized it’s really not too bad; much better than a lot of what’s out there. So I decided to print a few physical copies that I could sell at book fairs and book meetings I often attend. In those contexts, people want a physical book. They will politely take a flyer describing an ebook they can get online but they won’t follow up and order it.

Nook Press

I first turned to Nook Press, which recently launched a print publishing division (https://print.nookpress.com). My understanding is that they will soon spin this division off from Barnes & Noble as a stand-alone company to serve the market for making personal copies of a manuscript. What happens to all those millions of words generated during nanowrimo, for example? They have to end up somewhere, so Nook Press printing might as well get the print business.

I first turned to Nook Press, which recently launched a print publishing division (https://print.nookpress.com). My understanding is that they will soon spin this division off from Barnes & Noble as a stand-alone company to serve the market for making personal copies of a manuscript. What happens to all those millions of words generated during nanowrimo, for example? They have to end up somewhere, so Nook Press printing might as well get the print business.

I have already published Hunter and Hunted electronically with Nook (www.barnesandnoble.com/w/hunter-and-hunted-revised-edition-william-adams/1113980266?ean=2940016093451), and it’s listed for sale online with B&N. The print publishing arm of Nook will not get you a listing at B&N however. It is simply a way to print up a physical copy of your manuscript to impress your mother – B&N will not sell it.

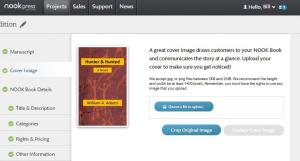

So fine, all I want for now is a few copies to hand-sell, so I went to the Nook Press print site, created an account, and signed in. The first thing I did was use their easy “Quick Quote” algorithm to see what this was going to cost me. I put in an estimated 250 pages, all black-and-white, using white paper and 6” x 9” trim size (the most common for novels), and I got back an estimate of $8.00 per book, plus an estimated $4.00 for shipping and handling, for a total of $12. That seemed a little high, but certainly not exorbitant, and there is no minimum order, so that would be my total cost for one printed copy of my book.

So fine, all I want for now is a few copies to hand-sell, so I went to the Nook Press print site, created an account, and signed in. The first thing I did was use their easy “Quick Quote” algorithm to see what this was going to cost me. I put in an estimated 250 pages, all black-and-white, using white paper and 6” x 9” trim size (the most common for novels), and I got back an estimate of $8.00 per book, plus an estimated $4.00 for shipping and handling, for a total of $12. That seemed a little high, but certainly not exorbitant, and there is no minimum order, so that would be my total cost for one printed copy of my book.

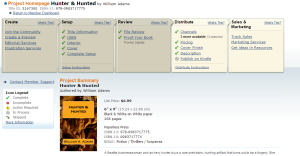

In the end, the actual book came out at 269 pages and cost $5.40 per book, with $5.50 shipping and $0.41 tax, for a total of $11.31 for one unit. Their Quick Quote prediction is relatively accurate overall.

Then the fun began. The first thing is to make sure that the manuscript is well-edited for spelling, grammar, and obvious formatting mistakes. Nook Publishing will sell you professional editing services for $300 to $1000 dollars, depending on the level of scrutiny you want. Since I am a cheap bastard, I took my chances with my own eyeballs. That’s generally not a good idea for most writers, because you can’t see your own work objectively. “What you meant” gets in the way of “what you said.” But I’ve edited this puppy a million times already, so I decided to go with that. Even so, on a final read-through, I made several changes, proving that the “perfectly clean” manuscript is a mythical object.

Next, I had to produce a print-ready PDF copy of the manuscript. You can start with a Microsoft Word document, then save it as a PDF and submit that to the Nook web site, which will automatically evaluate the format for suitability. It takes several tries to pass their evaluation. They provide a template set up with the proper margins, which is helpful, but still, there are innumerable tiny details to take care of, such as spacing, chapter headings, italics, and page numbers. It took me a couple of days to get a copy that Nook would accept. (They do provide a detailed formatting guide which helps avoid unending trial-and-error).

Then you need to create the book’s cover. Nook provides another template with the correct margins and a selection of photographs and background designs you can use. You have to position your title, author, and other information on the cover, to create a total cover design. Nook Press will sell you professional cover design service for $300 to $400, and that is probably a good way to go. Cover design is an art and a craft that mere mortals are generally not good at. But I am a cheapskate, so I uploaded my own photo and designed my own cover, all in Word, then saved as PDF.

Then there was the back cover, much easier than the front, but still a challenge. I used the Nook back cover template and positioned my back-cover blurb, my pricing information and ISBN, saving it as a PDF and uploading to the Nook site.

Then there was the back cover, much easier than the front, but still a challenge. I used the Nook back cover template and positioned my back-cover blurb, my pricing information and ISBN, saving it as a PDF and uploading to the Nook site.

When finally my three PDFs were accepted by Nook, I had everything in place. I reviewed everything, clicked my approval, and paid my $12. The book was delivered in about 10 days, and met my expectations. It looked good, inside and out, and was professionally manufactured. There were a few tiny errors (always!), such as, there should have been a page break between the final line of the body text and the “Author Bio” heading; the author photo was not high enough quality for print, and a few small elements like that. I would go back into the web site and fix those errors before I ordered multiple copies to sell. Overall, it was a good process that produced a reasonable product at a fair price.

Create Space

Next, I turned to CreateSpace, the division of Amazon.com that prints paper books on demand (www.createspace.com) in a similar way. I’ve had Hunter & Hunted listed on Amazon for sale as an electronic Kindle book for two years (http://www.amazon.com/Hunter-Hunted-William-Adams-ebook/dp/B00RBYZ47W/). This was a chance to let readers order a print copy if they preferred. Unlike Nook Publishing, CreateSpace is directly linked to Amazon’s distribution and sales network so when you create a print copy, customers can order it as a POD (Print-On-Demand) paperback from Amazon.com. This is a considerable advantage over Nook, if you’re interested in selling the book to the general public, because a lot of people prefer a physical book.

Next, I turned to CreateSpace, the division of Amazon.com that prints paper books on demand (www.createspace.com) in a similar way. I’ve had Hunter & Hunted listed on Amazon for sale as an electronic Kindle book for two years (http://www.amazon.com/Hunter-Hunted-William-Adams-ebook/dp/B00RBYZ47W/). This was a chance to let readers order a print copy if they preferred. Unlike Nook Publishing, CreateSpace is directly linked to Amazon’s distribution and sales network so when you create a print copy, customers can order it as a POD (Print-On-Demand) paperback from Amazon.com. This is a considerable advantage over Nook, if you’re interested in selling the book to the general public, because a lot of people prefer a physical book.

So I went to the CreateSpace site and signed in with my Amazon credentials and began the process of designing my physical book. I went through the same steps as I had done for Nook, except that CreateSpace has slightly different formatting guidelines, so basically, I had to reformat the entire text, changing manual page breaks into section breaks, for example. It wasn’t too difficult, using Word’s search and replace function but it was tedious and ultimately required a complete page-by-page re-proofing. CreateSpace also provides pre-formatted templates that take care of things like margins and trim size.

As with Nook, CreateSpace is happy to sell you professional editing services, interior design service, cover design, and so on, all for reasonable (but not cheap) prices. As before, I skipped all those and did it myself.

In the end, the CreateSpace formatting for the interior text was better-looking than for Nook, but it was more difficult to satisfy their criteria. For example, CreateSpace objected to a set of artifacts that Microsoft Word arbitrarily inserts into text (probably XML code) and which had to be hunted down and deleted – no easy task. The Nook system had simply ignored them. CreateSpace also would not accept my low-resolution author photo, which was a good thing – it wasn’t really sharp enough for a professional look. So I had to fire up my ancient copy of Photoshop Elements and do some bicubic resampling to increase the image density to the 300 dpi required by CreateSpace, and the result was a much better picture. So CreateSpace has more stringent criteria to satisfy, but in the end that forces you into a better product.

On the cover design, I had a similar problem. CreateSpace would not accept the low density of my chosen cover photo, even though I had used it on Nook and the result was perfectly fine. It was a photo of some petroglyphs, used as a flat background, and there is no need for the image to be pure and crisp. But CreateSpace wouldn’t take it, and I was unable to resample it without severe distortion.

On the cover design, I had a similar problem. CreateSpace would not accept the low density of my chosen cover photo, even though I had used it on Nook and the result was perfectly fine. It was a photo of some petroglyphs, used as a flat background, and there is no need for the image to be pure and crisp. But CreateSpace wouldn’t take it, and I was unable to resample it without severe distortion.

So I had to pick from CreateSpace’s offerings of cover layouts. I found one that worked okay for me, but the licensing was annoying. I have complete, unrestricted use of the photo for any CreateSpace – produced book. That means I cannot use their photo on a book I produced with Nook Printing, for example, and of course CreateSpace would not like me to use Nook Printing at all, would they? it’s a monopolistic lock-in. In the end, I decided to go with the CreateSpace photo, which was not as good as my own choice would have been, but I was already two days into the design and my patience was running out. This is another reason to consider purchasing a professional cover design, to avoid such forced choices.

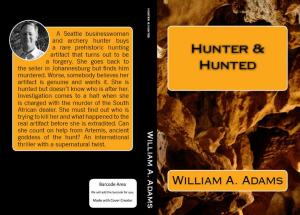

I then did the back cover design, which was quite easy, using CreateSpace’s template. Oddly, there was no template for the spine. CreateSpace provides a spine that cannot be changed, and I was not keen on it. The book’s title was in a small font, and the author’s name in a very large font (see illustration above) No doubt most authors are thrilled at that choice, but I wasn’t. Another compromise had to be made, so I accepted it.

I proofed the overall final design, changed a few obsessive details, and finally approved the design of the paperback, paid, and ordered one proof copy. The proof copy arrived just as expected except for the weird font size on the spine. The title of the book is in 8 point and the author name in 24 point. It’s ridiculous, bad-looking, and unnecessary. I dove back into the design software but was unable to find a way to fix that problem, so I had to redesign the whole cover with a different “theme” and completely different background photo. I also had to change my name! The new layout would not accept “William A. Adams,” without a word wrap, so I had to drop the middle initial. The new cover is adequate, though certainly not my first or even second choice. The “Cover Creator” software is basically Mickey Mouse. You can’t control the font at all. But the price is right (free).

Overall, I’d say that CreateSpace is a more thorough process than Nook’s, easy to follow, not always easy to satisfy, but produces a good product. My price per unit came out to be $4.30, about a dollar cheaper than Nook Press, with similar shipping, handling and tax charges. (What is “handling” anyway?)

Once your book design has been accepted by CreateSpace, the web site guides you through publishing on Kindle, showing the cover you designed. I went through that process then deleted (“unpublished”) my old Kindle version, so there would not be two different-looking copies of the same ebook.

The web site also steps you through distribution and pricing decisions. I decided to price the paperback at $6.99, which gives me a 70% royalty (of 13 cents!) in the USA and most other countries, 35% in the rest. They want you to sign up for some exclusive deal with Amazon in order to get 70% payout across the board, but I didn’t want that. I’m not in it for the money. Besides, I sell more ebooks books through Smashwords.com than I do through Amazon, so I am not motivated to restrict myself to Amazon. Amazon manages to keep more of your money, but hey, they’re Amazon.

The web site also steps you through distribution and pricing decisions. I decided to price the paperback at $6.99, which gives me a 70% royalty (of 13 cents!) in the USA and most other countries, 35% in the rest. They want you to sign up for some exclusive deal with Amazon in order to get 70% payout across the board, but I didn’t want that. I’m not in it for the money. Besides, I sell more ebooks books through Smashwords.com than I do through Amazon, so I am not motivated to restrict myself to Amazon. Amazon manages to keep more of your money, but hey, they’re Amazon.

In the end, I now have a newly-designed Kindle book in the Amazon Kindle store, and a customer can also order a paperback copy if preferred (www.amazon.com/Hunter-Hunted-William-Adams-ebook/dp/B00ROBHZR4/). In addition, I can order a dozen or so copies of the paperback at my cost, which I can then sell at book fairs. Despite the annoying monopolistic practices of Amazon, it turns out there’s a reason why they dominate bookselling in America. They make it easy. To produce print copies just for my own use, I would probably use Nook Press instead, which is a lot more flexible process. But to sell books online, CreateSpace has the game sewn up.

McCarthy, Cormac (2006). The Road. New York: Knopf (306 pp).

McCarthy, Cormac (2006). The Road. New York: Knopf (306 pp).