A milestone for any project is first words written. Page one, Chapter one: actual words. They are probably not the right words, but you have to start with words in sentences.

A milestone for any project is first words written. Page one, Chapter one: actual words. They are probably not the right words, but you have to start with words in sentences.

The sequel I’m working on now will be my sixth novel. My experience has always been that the first words I write are not the right words. I already know the first chapter is completely wrong and will have to be deleted or rewritten and relocated. So I’m under no illusion that I have really written the first words of the new novel, but I don’t care at this point. Staring at a blank screen is such torture that I bless the 700 words I wrote today and I will build a castle on them.

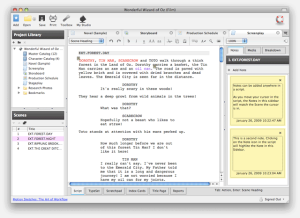

The method I’ve developed over the years to overcome the sheer pain of blank screen syndrome is somewhat elaborate and time-consuming, but I’d rather do it than stare helplessly at the screen.

I start with a cast of characters, as described in another post, and develop a biography and a personality for each main character. That takes a couple of days for the characters I will need in Chapter One. I do other characters as they come up.

Then I turn to a template for the sketch of a new chapter. It asks for the title (always TBD) and the start date, because I feel very satisfied when I put the “finished” date on it later. Then the template requires me to write the goals for the chapter. What do I hope to accomplish with it?

For Chapter One of anything, the goals are to introduce the MC and the status quo, but that’s too general. Those outcomes will be accomplished as side-effects of what the characters say and do. So really, what I’m looking for is HOW do I expect to accomplish those goals.

I drop down to the next section, “Plot Points.” There, I describe at a high level what action will take place, and where, and who will be involved. “Robin comes home early from work and finds Sid with another woman.”

To flesh out that action (so to speak), involves several days of research because for Chapter One, I don’t even have complete names for the characters yet and locations are only vague geographical references. So I go into a long, tedious search of my “character names” files, developed over the years to collect interesting first and last names in scores of ethnicities and time periods. I also use online references like http://names.mongabay.com/most_common_surnames.htm to find good names. I like names to be suggestive of the characters’ personalities, and I like first and last names to be easily pronounceable, sonorous, and highly distinct from each other. If there’s a Robin, there will be no Rachel, not even a Robert. I’m fond of alliterative names but that can get cute so I have to check myself. Finally when I have character names, I write several choices into the chapter outline, because the one I prefer today, I’ll probably hate tomorrow.

For locations, I use City-Data (e.g., http://www.city-data.com/city/San-Francisco-California.html to make sure my characters are living and working in the kind of neighborhoods I want them to be in. Then it’s a long session with Google Maps, Google Earth, and Google Street View to find a house and a job for each one and work out transportation logistics. I hate it when I change my mind about a location because that involves at least another hour of research but sometimes it has to be done because I’m not getting satisfaction.

Once I have geography I have to do buildings and cars. I have a list of reminders to ask myself about colors, textures, smells, lighting, sounds, temperature, meanings (to the characters) furniture and visual space – it’s a long list. I don’t always fill out every detail, but I specify enough so I have a feel for the locations, exterior and interior, where my scenes will take place.

Once I have space, I need time. I have to decide the season of the year, the time of day, the weather, temperature and lighting conditions.

Next, I need a list of scenes that will fulfill the main plot points listed above. In this example, I might decide to start with Robin on the drive home from work so she can ruminate on things by herself for a few minutes. That introduces some of her attitudes. Then I need a short scene where she arrives home and notices things out of place, then an awkward scene where Sid is busted, then a tense scene where the other woman appears and is kicked out by Sid, then a very excruciating scene where Robin and Sid “discuss” what has happened, then a quick exit scene that gets Robin out the door.

I make that list, and make sure the order is what I want. It may turn out that I have too much. I like chapters to be short, between 2K and 3K words, rarely over 12 pages or so, but scenes tend to take on their own life and I just have to go with that. The number and length of scenes is ultimately empirical.

Finally, I need or want some narrative foot-in-the-door opener. I like to start a chapter with the 3P narrator’s voice (or alternatively, a 1P character pontificating a bit), along the lines of “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.” That helps me establish my narrator’s voice and gives the momentum to get rolling. It doesn’t always work out, and it always risks running too long but I like to do it.

I deliberately avoid starting with the weather, the scenery, and waking from a dream or even a sleep. I also don’t like starting with a direct quotation because it will necessarily be out of context. I don’t start with manufactured drama by using unresolved pronouns. Faulkner did that a lot and I disliked it. It seems manipulative, even hostile. I like to start with a snappy generalization that I can parse subsequently in the MC’s mind, using free indirect discourse if necessary, but I can also start with description of high action, if appropriate.

I confess that today’s precious 700 words of Chapter One are entirely narrative description mixed in with the MC’s thinking. It’s probably too much, but you can’t edit nothing, so I’m leaving it for now. When I finally got Robin into the kitchen and ready for the first focused-camera scene, I stopped, and started writing this post instead.

I started writing this because I was so relieved to have, once again, overcome blank screen syndrome, which I really, really hate, and I stopped also because to write an actual scene with action, characters, and dialog – I don’t just flow into that. Each scene takes further preparation and my cortex was blown for the day.

But at least I beat the blank screen syndrome! Yay. I’ll start tomorrow by going over that narrative introduction, cutting it back and adding more physical description for my MC, which I always tend to overlook. Then I’ll sketch my first scene before I write it.

This method, chopping the wood before lighting the fire, works for me. It’s mentally exhausting, but it gets words on screen. The tragic part is that every single chapter starts with the same blank screen and the whole process must begin again. It’s July now. Can I get a draft done by Christmas?

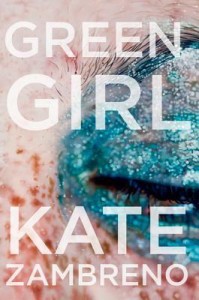

I just read and reviewed Green Girl, by Kate Zambreno. See it here.

I just read and reviewed Green Girl, by Kate Zambreno. See it here.

Seven chapters have miraculously appeared as the start of my new novel (although Chapter 7 has to be significantly rewritten to accommodate my plan for #8 – I hate when that happens). Regardless, I’m starting to enjoy my characters.

Seven chapters have miraculously appeared as the start of my new novel (although Chapter 7 has to be significantly rewritten to accommodate my plan for #8 – I hate when that happens). Regardless, I’m starting to enjoy my characters.