I just finished re-reading Art &Lies by Jeanette Winterson and was again elevated by her lyrical language, though unlike my first awe-struck read, about four years ago, this time I noted more over-writing and self-indulgent wordplay – not that I could ever do any better with the language than she.

I just finished re-reading Art &Lies by Jeanette Winterson and was again elevated by her lyrical language, though unlike my first awe-struck read, about four years ago, this time I noted more over-writing and self-indulgent wordplay – not that I could ever do any better with the language than she.

I realized this time however that the book is only marginally a “novel.” It has a very loose story, actually four of them, as the main characters move through time, interacting only tangentially and unknowingly. There is an overall theme, stated by the title, but no real throughline, no real plot. It’s a set of prose poems, or a set of literary essays on sexuality, gender relations, art, religion, and society. Still, I thought it was a successful book, whatever it’s called.

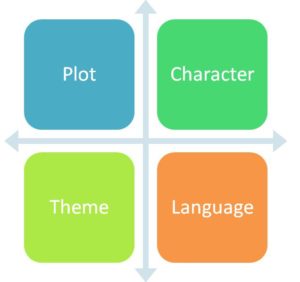

So what are the essential elements of a successful book-length work of fiction? I came up with a quadrangle of essential elements and sketched them in my notebook as a square, but a four-point list conveys the same:

- Plot. Good fiction has a clear story structure with beginning, middle and end.

- Character. Good fiction has unique, interesting, relatable characters.

- Language. The best stories use language interestingly or at best, thrillingly.

- Theme. A memorable story has a point, a moral, a self-transcendent theme.

Among these, plot is easily sacrificed, maybe not entirely, but in large part, as it was in Winterson’s Art & Lies. Often, in literary fiction, the plot is very sketchy, almost pure contrivance, just enough to make the story stand upright. Other examples include The Sun Also Rises and The Sheltering Sky.

Conversely, very strong and obvious story structure, a plot dwarfing the other three elements, is easy to come by, the definition of bad genre fiction. There is a range of quality of course, as with everything. A book like Dracula is plot-driven yet still, there are interesting characters.

Character is difficult to dispense with, though bad genre fiction manages to minimize character for the sake of plot. Many extremely popular thrillers take this tack and millions of readers don’t seem to mind if the characters are hollow puppets, merely cartoon cutouts. Indeed, many of the most popular movie characters these days are literally cartoons and somehow they command large audiences.

At the other extreme, a very “character-driven” story is one in which the main character’s development or “arc” as we like to say, is the dominating feature, even at the expense of plot. The character is so compelling that we don’t really care much how the nominal story line goes. Much so-called literary fiction is defined in that way. Examples that come to mind are Rabbit Run, Under the Volcano, Mrs. Dalloway, The Road, Dubliners, Reservation Blues, Remains of the Day. Most of those stories have a nominal plot but the focus is on how the characters live, suffer, and triumph. We don’t really care much about who captures the brass ring.

The most successful fictional stories combine strong characters with strong plot. The classic example is Oedipus Rex by Sophocles. In such cases, plot is character, as they say. The events of the story are driven by the character’s intentionality, and in turn, the character’s reactions are provoked by story events in equal measure. Other examples include The Third Man, Olive Kitteridge, Winter’s Bone, Sanctuary.

The most successful fictional stories combine strong characters with strong plot. The classic example is Oedipus Rex by Sophocles. In such cases, plot is character, as they say. The events of the story are driven by the character’s intentionality, and in turn, the character’s reactions are provoked by story events in equal measure. Other examples include The Third Man, Olive Kitteridge, Winter’s Bone, Sanctuary.

The third corner of the square is language. When language is dominant at the expense of the other three elements, the story is written with such lyrical, unique, uplifting or engaging language and imagery that we barely take notice of the plot and we connect to the characters only enough to keep the language flowing. Art & Lies is one of these. Lolita is another (although some people find that thematic material compelling – I didn’t). Other examples of language and image -driven fiction include As I Lay Dying, The Sellout, The Lover, Skinny Legs and All, Coming Through Slaughter, Gould’s Book of Fish, Hard-Boiled Wonderland.

Language-only-driven fiction is the most difficult to justify, in my view. Why not just read poetry if elevated diction is what you’re interested in? The very best novel will have good writing, of course, but it is possible to overinflate the language corner of the quadrangle while diminishing the other three angles.

Theme is routinely dispensed with in genre writing, or else the thematic elements are extremely broad and obvious, fairy tales with “a moral” rather than with an implicit proposition that makes a comment on the nature of human life. The best novels make strong, though usually implicit, thematic statements. Examples include Beloved, Barbarians, Ceremony, Woman in the Dunes, Geek Love, Slaughterhouse Five.

Sometimes the theme is heavy-handed but still largely effective, such as in Orlando, Disgrace, Wittgenstein’s Mistress, Animal Farm, No Exit. Sometimes it is exceptionally subtle, such as in One Hundred Brothers, Let the Great World Spin, The Third Policeman, Haroun and the Sea of Stories, Housekeeping. Unfortunately, thematic material is the most difficult for most readers to discern and assess and that keeps them away from most literary fiction, which tends to be thematically laden.

If a story does not have much of a theme, or if the theme is slap-in-the-face obvious, usually it’s genre writing. Genre novels are all about plot, and any thematic message usually takes simple-minded form, such as “good triumphs over evil.” Novels that have no theme at all end up seeming pointless, as genre writing often does. A recent popular example would be The Martian.

I don’t know if I’ve ever read a novel that rang all four bells loudly. I don’t know why that is. Maybe it’s impossible to write. The very best ones, and the kind I would like to write, hit three out of four, but even two out of four can be successful, and rarely, just one out of four. Art & Lies is successful thought it has almost nothing going for it except language. Lolita has brilliant language and a very weak story line. The thematic line is so heavy-handed, it’s best to ignore.

However, I think some combinations work better than others. Strong plot and character (no language and theme) works. Plot and theme only (weak character and language) is less satisfying. Examples include Middlesex, Blindness, The Collector.

I used to start with plot when I began a new project. I am still plot-biased, but now I focus much more strongly on character, and lately, also on theme. I’ve given up on ever being able to write lyrically. I think I was poisoned by a lifetime of writing academic nonfiction and even after many courses and books in how to write poetry, I don’t believe I’ll ever have the patience to write poetically, even though I admire it when I read.

We can do what we can do and no more.