The Orphan Master’s Son is a grim book with a high gross-out factor, so if you don’t tolerate torture and gore well, it wouldn’t be for you. But if you enjoy the creativity of trying to depict sheer horror, it’s great.

The Orphan Master’s Son is a grim book with a high gross-out factor, so if you don’t tolerate torture and gore well, it wouldn’t be for you. But if you enjoy the creativity of trying to depict sheer horror, it’s great.

The story is set in North Korea and describes, with considerable exaggeration, the lives of deprived citizens, brainwashed and near-starvation, and also life among the secret police in their dungeons, and also life at the top of the political elite with their wealth and privilege.

Though well-researched, the novel is fiction, a work of literary art, a fable, a self-expression, a satire, a morality tale, a fairy story. It is not a travelogue and not a political essay. It seems necessary to say that, since nearly all reviews treat it as a travel essay and judge it by its degree of adherence to realism.

Questioning the nature of realism is the point of the novel. What is real and what is social fiction? State-created fiction especially affects the lives of its citizens even in America, with its “American Dream.” Any child can grow up to be president, right? If you work hard and honestly, you will enjoy success. All men are created equal, democracy allows people to express their political will, the free-market insures fair play, religion has no role in government, nobody is above the law, the guiding principle of America is freedom, America only goes to war as a last resort and in self-defense, the news and entertainment media are independent and free…

Why would mythmaking be any different in North Korea, where you have the additional advantage of loudspeakers in every public place and every apartment constantly spewing government propaganda, where all information media are state-controlled, where borders are closed and the economy is centrally managed? North Korea is the perfect setting to ask the question, of any culture, what is real and what is mass delusion? And the corollary: without that delusion, who would I be?

The first third of the book is narrated in third-person-close, close to the main character Jun Do, an orphan (he discovers later) helping his “father” run an orphanage in a small, desperate village. Eventually, to save face in an embarrassing international incident, he is acclaimed a hero and sent to English school and summoned to Pyongyang for glorification. He knows he’s no hero, but wait, maybe he is. If everyone says you’re a hero, why would you not be?

The “legend” defines the person. That fact is made in a grotesquely and darkly comic way in this novel, but isn’t it also the truth around the world? If you’re a rich CEO and everyone defers to you, you are smart, virtuous, exceptional, and chosen. The proof is that you’re a rich CEO. Myth is reality. Johnson uses the crude instrument of North Korean propaganda to make that point with a broad brush.

The second two-thirds of the tale is told by three narrators taking turns, which conveys the confusing fragmentation of multiple social roles, and of North Korean society. The main, third-person narrator is now close to Commander Ga, right hand man to the Dear Leader, but in a series of flashbacks we understand he is an imposter. Actually he is Jun Do, who was sent to a death camp, where he stole the identity of the real Commander Ga and escaped. But even though he looks nothing like Commander Ga, his story is that he is Commander Ga, and who is to say otherwise? The story is the man.

A second narrator, first-person, is an interrogator and torturer with the secret police. He seems to have the real Commander Ga in captivity. The story is the man, but they don’t have the prisoner’s story and that’s the trouble. What use is a person without his story? They need to torture the story out of him.

The third narrator is the state propaganda voice on the loudspeakers, which operates like a Greek chorus in the ancient plays, commenting on the story-in-progress, elucidating its meanings and values. The loudspeakers’ story creates distance on the ongoing story of the “fake” Commander Ga and his actress wife as they plot their defection. It is a creepy and weirdly disorienting voice that reminds me of the mood in Don DeLillo’s White Noise.

Unfortunately, the story devolves into a confusing sentimentality that belies the tensions so carefully established. Only Kim Jong Il and the voice of the loudspeakers stay in character. All the others rip off their masks and say to the reader, “Ha-ha, fooled you!”

So the novel does not remain true to itself as satire, or as a political indictment, or as a traditional morality tale, and despite some superficially dramatic scenes, the ending falls flat. But taken as a whole, the journey is an extremely well-crafted, artistic exploration of multiple questions about life as an individual in a state-controlled society (as we all are). Well-worthy of the 2013 Pulitzer Prize.

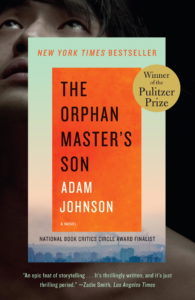

Johnson, Adam (2012). The Orphan Master’s Son. New York: Random House 443 pp.