Interesting writing kept the pages turning for me. Nguyen has a knack for unexpected description and creative simile. A random example: Two men are talking but notice the chairs:

Interesting writing kept the pages turning for me. Nguyen has a knack for unexpected description and creative simile. A random example: Two men are talking but notice the chairs:

“As usual, he reclined in an overstuffed leather club chair that enfolded him like the generous lap of a black mammy. I was equally enveloped in the chair’s twin, sucked backward by the slope and softness of the leather, my arms on the rests like Lincoln on his memorial throne.” (p. 63).

The protagonist is the son of a French father and a Vietnamese mother. He works for North Vietnam, but lives in Saigon as a mole in the South’s secret police. He barely escapes the fall of Saigon then after some tribulation thrives in the Vietnamese expat community in California, still tightly connected to the pro-American, pro-democracy military crowd there. While ostensibly helping “the general” and other officers plan a return and counterinsurgency in Vietnam, he sends secretly encoded messages back to his controller in Ho Chi Minh City.

The hero, known as “The Captain,” is a divided self. He has mixed heritage and is sensitive about that, feeling he is never quite accepted either by the Americans or by the Vietnamese. That ambivalence parallels his secret spy status, acting as both communist and democrat, and again by his sensibilities, appreciating the American way of life, American music and scotch, and also despising the American military for having betrayed his country, abandoning it at the end. He is a two-sided man.

Much of the dark, sarcastic humor of the book arises from his dissociated observations.

“As the Congressman rose, I calmed the tremor in my gut. I was in close quarters with some representative specimens of the most dangerous creature in the history of the world, the white man in a suit.” (p. 250).

“The General furrowed his brow just a bit to show his concern and understanding. As a nonwhite person, the General, like myself, knew he must be patient with white people, who were easily scared by the nonwhite. Even with liberal white people, one could only go so far, and with average white people one could barely go anywhere.” (p. 258).

While the writing is consistently engaging, the story is close to nonexistent, the characters not cleanly drawn, and the pace a terrible sag. That makes the book very slow going, indeed.

The humor doesn’t sustain or redeem it. A lot of pulled punches pass as humor but merely ridicule clichés and stereotypes. Every conceivable American stereotype about the Vietnamese people is trotted out and lambasted, including a tedious, extended parody of the movie, Apocalypse Now.

Was that really necessary? We get it. Stereotypes: bad. Unlike the self-effacing and creative ethnic humor in a book like The Sellout by Paul Beatty, Nguyen doesn’t seem to have much distance on ethnic prejudice and expects the reader to be shocked when he calls it out.

As a commentary on politics and history, the book is sometimes interesting but lacks deep insight. For all his supposed commitment to communist ideology, for example, “The Captain” doesn’t have much to say about the relative virtues of communism and capitalism, other than to note the obvious differences and to convey an obvious conclusion, exploitation: bad. The tragic political history of Vietnam is treated in similar superficial matter. Colonialism: bad.

The story line does have a few plot points, although anyone wanting to tighten it (e.g., a screenwriter) would have to cut at least 150 pages of plodding quotidian detail. Endless drinking, smoking, and sex do not a compelling story make.

Towards the end the story picks up a bit when The Captain and a band of pro-American soldiers return to the country to try to stir up revolution, but The Captain seems strangely unaffected by his dual allegiance. His thoughts and feelings don’t ring true.

The Captain is a divided character, but I didn’t feel that tension, which was only stated, rarely shown, even when he had to kill an innocent man to “prove” his bona fides. Yes, the ghost of the dead man haunts him (tediously) for the rest of the novel, but that fact still doesn’t reveal the Captain’s inner conflict. If he was so conflicted, why did he do it? If he did it against his better judgment, why? Does it change him as a person? I wasn’t “feeling” the Captain.

The guts, gore, and torture in the last hundred pages seemed gratuitous, considering how the first part of the novel was set up to be a Lolita-like, self-reflective and self-exculpatory confession.

The ending is superficially dramatic but in fact hinges on an old Buddhist joke. A monk opens a birthday present and finds the box empty. What does he say? “Nothing! Just what I’ve always wanted!”

The book is well-enough written that it can live up to its Pulitzer Prize, but I don’t think it will stand as a landmark in literature.

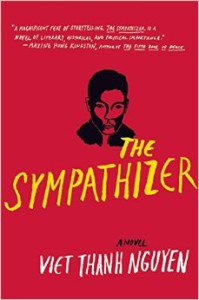

Nguyen, Viet Thanh (2015). The Sympathizer. New York: Grove Press (385 pp).