Everyone dies. A significant number of people will die in automobile crashes, gang wars, from drugs, or in military wars, but because of modern medicine and public health, if you live through your twenties, you’ll probably die of “natural causes,” which is to say, of the diseases that come with old age. And how does that go? Usually not well.

Everyone dies. A significant number of people will die in automobile crashes, gang wars, from drugs, or in military wars, but because of modern medicine and public health, if you live through your twenties, you’ll probably die of “natural causes,” which is to say, of the diseases that come with old age. And how does that go? Usually not well.

Hospitals are motivated and incentivized to keep you alive at almost any cost (your cost, not theirs). I’ve seen relatives and friends linger on, year after year, hanging by a thread it seems, but not dying, until the money runs out and the medical care stops.

Besides the financial crunch of getting old, the human cost is incalculable, both to the dying person and those who care for him or her. Quality of life declines rapidly. Freedom is lost. Choices are constricted. The body becomes frail and unreliable, and so does the mind. There is nothing quite like seeing the terror in someone who realizes they are losing their mind and knowing it will get worse, never better. Medicine and medical care become ever-more extreme and expensive. Pain, discomfort, and anguish increase exponentially. Every day is a crisis. There’s nothing good about modern dying.

As for family caregivers – it’s a life-changer. Untold hours and dollars are expended. Personal plans and goals are suspended for years. Family life is severely disrupted. Intra-family battles erupt. Relationships are strained. Choices narrow. Guilt and depression are common. High-stakes, high-anxiety, battles with hospitals, doctors, insurance companies, banks, lawyers, assisted living centers, rehab centers, hospices, pharmacies, the IRS, DMV, and even the post office, are unrelenting. The collateral damage is severe.

America has no rational infrastructure for dying other than capitalism. As long as someone is still breathing, they are “alive” and that’s all that matters. Quality of life, physical, mental, social, and spiritual, do not figure into any assessment of dying and consequently, and unconscionably, all of those aspects of living are depleted despite the cost in human suffering.

If you want to die on your own terms, instead of slowly slipping into uncomprehending pain and frailty, sucking your whole family into the vortex with you, then you need to plan ahead. You will die. There should be no surprise there. The question is whether you will do it your own way.

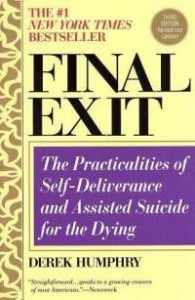

“Final Exit” is for people diagnosed with terminal illness who would rather die in a manner of their own choosing instead of going through the traditional meat-grinder of the health system in America. It describes how to establish a “living will,” which instructs health care professionals and family members what your wishes are, and other useful steps, such as providing a trusted family member or other person with power of attorney to manage your affairs. All this can be set up in advance, when you are happy and healthy.

The book also offers advice about whether or not to end your own life, either with the help of a physician (“assisted suicide,”) or on your own. Assisted suicide is available in three states now, WA, OR, and MT, for residents only, and the regulations are stringent. You really do have to be within your last six months of life due to untreatable, terminal illness. It is not for “mere” old age.

Author Humphry (a physician) is keen to state that the book is not meant to assist people to commit suicide, especially people who suffer from depression, other mental illness, or a severe reversal of fortune. It is advice for, as he calls it, “self-deliverance,” the act of an irreversibly ill person to make a rational, voluntary decision to end life.

The book is somewhat controversial because some people believe there is no such thing as a rational, voluntary decision to end life. If you make such a decision, you are, by definition, suffering from mental illness. If that’s what you think, then don’t read this book. It assumes that when and how to die can be a rational and moral choice.

Religious people may object that only god can determine when and how each person dies. Of course if that were true, they would eschew end-of-life care, but they don’t. If you believe the god-knows-best argument about death, this book is not for you.

Two philosophical problems remain however, even for those who believe that when and how to die can be a personal choice.

One is that, when you’re depressed, you often don’t know you’re depressed. You might be better served by counseling than suicide. The only way to know is to talk it out with family members, counselors, and people you trust. You cannot make a decision about suicide yourself. If you really are completely on your own, you’re in a conundrum and could make a terrible mistake. The book does not address that possibility adequately.

The second problem is that the book insists you have a “right” to die the way you choose to, but that is incorrect. There is no such right. Rights are granted to individuals by the social matrix of a community, sometimes personified by an acknowledged authority, often encoded into law. Since society generally disapproves of suicide and murder, it is wrong to conclude that you have any right to take your own life or have anyone else help you do it. The book is not clear about the role of the value systems in the society that an individual lives in. It assumes you have some vague magical “right” of self-deliverance, but you do not, so it will be an anti-social act if you go through with it and you need to be aware of that from the start.

Putting that prologue aside, the book is valuable in describing how to “deliver” yourself and how not to. It advises, for example, to rule out any kind of plant or chemical poisons. You probably won’t die from them and probably will end up with brain damage. Same with sucking exhaust from your car. Not effective. Same with most drugs you can get, either illegally on the street or legally from your doctor. They’re not pure or they’re not strong enough, or they have anti-suicide technologies built into them. You can’t know what you’ve got or if it will be effective (lethal). It’s not that easy. There is no suicide potion you can count on.

The most direct method of delivering yourself, and by far the most common, is gunshot. That’s extremely violent and messy however, not available to everyone, especially not for the frail and/or faint-hearted. It’s also not guaranteed to be done right. It’s just the most obvious. The book does not discuss self-inflicted gunshot as a method, an odd omission, considering its frequency. Is there a better way?

The book lists dozens of pharmaceuticals that would be effective, along with the dosages needed and the probability of lethality. However, as a practical matter, you probably can’t get those drugs in the purity and quantity needed.

The recommended choice is the old bag-over-the-head method. A plastic bag, taped at the neck, brings death by asphyxiation in thirty minutes to a few hours, provided you don’t tear it off in a panic when you realize you are actually dying. The recommended method is to take an overdose of sleeping tablets (which are not lethal in themselves anymore), perhaps along with alcohol and an anti-emetic, so that you are fast asleep before you suffocate and therefore won’t panic (hopefully) before the process is complete. No data are presented on success or failure rates of the plastic bag method, an odd omission, considering its recommendation.

A much simpler and more obvious method is to ask your doctor to prescribe something lethal for you. Given your circumstances, you might be surprised at how accommodating the physician might be. Of course you have to use indirect language. No doctor is going to agree to murder or accessory to murder. But it is possible to make your meaning clear without being direct. I have seen that approach work with a relative who was in hospice care.

You will need more and better information than this book provides in order to make your own plan for “self-deliverance.” Judging from the outdated pharmacological information in the book, I’d say it is a good introduction to the topic but “The Final Exit” is not the final word.

Humphry, Derek (1991/2005). Final Exit: The Practicalities of Self-Deliverance and Assisted Suicide for the Dying. New York: Delta/Random House, 224 pp.