Ta-Nehisi Coates Meets Thomas Pynchon

“Who am I? And how can I be that person?” Those were the questions the main character’s father always asked and which the narrator, Bonbon Me, holds dear. They’re also the meta-questions he poses about black identity in America. His father was gunned down in the street by police.

Bonbon says, “Now, if I had my druthers, I couldn’t care less about being black. To this day, when the census form arrives in the mail, under the RACE question I check the box marked ‘Some other race’ and proudly write in, ‘Californian.” Of course, two months later, a census worker shows up at my door, takes one look at me, and says, ‘You foul nigger. As a black man, what do you have to say for yourself?’ And as a black man, I never have anything to say for myself….So I mumble Sorry and scribble my initials next to the box marked ‘Black, African-American, Negro, coward” (p. 44).

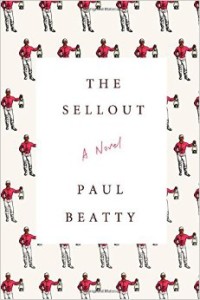

That excerpt summarizes the theme and the tone of The Sellout.

The humor is complex. It’s satire, using wit and scorn to criticize black feelings of inferiority, white privilege, racism in America, government mendacity, and political correctness. It also depends on wonderful wordplay, often erudite, often just plain silly, with remote associations that consistently violate expectations. That’s the basis of my comparison to Thomas Pynchon’s writing. And Beatty’s writing is the kind of self-effacing humor that is the bread-and-butter of good stand-up comedians.

The novel reads like a stand-up routine, multiple vignettes loosely threaded. The through-line is that the protagonist vows to reconstitute his lost childhood neighborhood of Dickens, an imaginary district somewhere in south or east Los Angeles. He paints boundaries on the street with white paint and puts up official-looking signs, “Welcome to Dickens.” Residents scorn his foolishness at first but eventually become proud. What kind of a town is Dickens? Segregated, he decides, and goes about putting up appropriate signs, such as one on the local bus that reserves seats near the front for “The disabled, and whites.”

Improbably, Bonbon also owns and operates a stables and vegetable farm within the urban district, violating “hood” norms and making him a sellout, part of the landed gentry. Worse, he owns a slave, an old black man who wants to be a slave because he’s nostalgic for the simpler days of overt racism and segregation when black people knew their place. Oddly, there is no law in the U.S. against owning slaves, which Bonbon discovers when he has to defend himself in court.

In the end, Dickens is recognized, by the weatherman on TV at least, as a legitimate, named township, so the hero triumphs. But that plot line was extremely weak and not really the point of the novel anyway. It’s not a “story” kind of novel.

Toward the end, Beatty starts to spell out some of his themes more explicitly, as in this excerpt:

“… A giant photo of Michael Jordan shilling for Nike is projected on all four walls of the courtroom, but it’s quickly replaced by successive photos of Colin Powell sharing his recipe for yellowcake uranium before the United Nations General Assembly shortly before the potluck invasion of Iraq and Condoleezza Rice lying through the gap in her teeth. These are African-Americans meant to illustrate his point. Exemplars of how self-hatred can compel one to value mainstream acceptance over self-respect and morality” (p. 275).

Even when the author gets a little heavy-handed, as in the above excerpt, and even when his thematic outbursts about black identity get repetitive, I’m still with him because of delightful surprises like “lying through the gap in her teeth.” How does he consistently come up with stuff like that?

The rich humor never let up, in my opinion, and while the theme of black self-hatred became obvious and overdone early in the book, there are still larger themes to think about, such as whether political correctness has gone too far. Yes, racism is ugly and ever-present, but it’s a legitimate question to ask, how we will know when to declare that we’re “over” the great historical traumas? The society is never really going to be post-racial, because humans are tribal in their bones, but do we need to keep replaying old “Little Rascal” films forever?