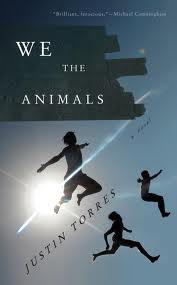

Torres, Justin (2011). We the Animals. New York: Houghton-Mifflin/Mariner

This short novel (125 pp) is fronted by 9 pages of superlative blurbs by reviewers, a sure contrary indicator for me. That means the publisher felt the need to tell me it’s a good book because I couldn’t be trusted to decide that on my own. True enough in this case.

Three brothers, 7 to 10, grow up in an impoverished Puerto Rican family in New York. The 19 “chapters” are just unconnected scenes, vignettes without any story arc. Over the course of these snapshots, especially toward the end, the boys are older, and one of them, the first-person narrator, reveals his gender-identity secret. In that sense, the work could be construed as a coming-of-age story for the unnamed narrator.

The language itself is ordinary, not lyrical, but the descriptions are imaginative, energetic, and vivid, and that is the book’s main attraction. Here is a sample taken randomly, expressing how the neglected children ate:

“We ate peanut butter on saltine crackers and angel hair pasta coated in vegetable oil and grated cheese. We ate things from the back of the refrigerator, long-forgotten things, Harry and David orange marmalades, with the rinds floating inside like insects trapped in amber. We ate instant stuffing and white rice with soy sauce or ketchup.” (p. 30)

The mother was pregnant at 14, seems to be alcoholic now, and works at a brewery. The father hustles in vague deals as he can. The brothers are the animals, fighting, prowling, skipping school, breaking windows, always on the edge of trouble. A band of pirates or Musketeers, they call themselves.The author keeps the bond tight among them by frequent use of the first-person-plural voice which creates a sense of a communal consciousness, much as Julie Atsuka did in Buddha in the Attic.

Many of the vignettes are exercises in pure sentimentality, a favorite trope being one where a stranger acts kindly to the three menaces, because they are “adorable.” In one scene, the brothers pool their pennies to buy a half-pint of milk for a stray cat (the shopkeeper lets them have it even though they don’t have enough money – because they’re adorable), and they literally save the cat. What could be more precious?

Another adorable trait of the brothers is precocious thoughts and language. From time to time they explain death, or God to each other, or invent a fantasy about an anti-gravity device that would let them fall right up to heaven. Is that cute or what?

In the last two chapter/scenes, the narrator is much older and reminisces on childhood, especially in a jarring switch to an unidentified third-person voice that seems way out of place. At the end, after having reverted to first-person, the narrator suddenly becomes second-person, addressing the reader directly, as he goes into a dissociative fugue. It all seemed desperately writerly to me.

Overall, I took away a sense of “a life,” one different from mine, different from that of most middle class book-buyers, I would guess. But it seemed to have no point. The story doesn’t illuminate anything, like Claude Brown’s Manchild in the Promised Land did, for example. The book is lauded as autobiography, but if so, it falls short of explicating its subject. If it was a novel, it doesn’t have enough to hold it together. Nor does it have the lightness of language to make it airborne as prose poetry, like Marguerite Duras’ The Lover. It’s a hybrid form, whose purpose is not clear to me.