We’re All Storytellers

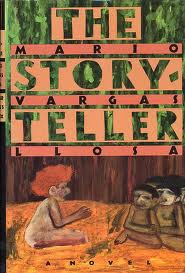

Llosa, Mario Vargas (1989). The Storyteller. Helen Lane (trans.) New York: Farrar, Strauss, Giroux

An unnamed first-person narrator, traveling in Florence, tells two stories. One is about his lifelong fascination with the pre-industrial, unacculturated tribes of the Amazon basin, in Peru. He describes having gone upriver to study the tribes in his youth. The second story is about his college-years friend, Saul, who was equally fascinated with the premodern tribes but who disappeared mysteriously, only to be discovered later as having “gone native” and joined one of those tribes as a quasi-shamanic storyteller, one who serves as messenger, bard, and collective memory for the tribe.

Interspersed with the narrator’s tale is another set of stories told by another first-person narrator, who we eventually learn is Saul, speaking as a native storyteller, relating the indigenous cosmology and myths and also telling his own tale of how he became a storyteller.

The book closes with the original narrator musing in perplexity: How could a modern person go back to a premodern condition? How would it be possible to go from science to magic, from reason to animism, from progress to timeless myth? Ironically, he is a Peruvian himself, but he asks these questions while in Florence, surrounded by European Renaissance art and architecture. He also doesn’t deliberate on the Spanish conquest of the Peruvian Incas in the 1500’s, which led to the modern culture which he claims as his own. Further, he does not seem to be self-aware that as the narrator of the framing story he is himself modern storyteller.

As an ethnographical essay, there is much food for thought here. Are premodern cultures “primitive?” Are they “living history?” Should they be preserved, or allowed to assimilate? What do they want? Is their absorption by the dominant, invading culture inevitable? Is it wrong? Is there “good” cross-cultural contact (medicine and tools) and “bad” contact (disease, exploitation, religious evangelism)? What is the ethical responsibility of anthropologists when studying a new culture? These and many other questions are worthy of consideration. I’m not sure if they constitute a novel.

Some readers might find the native myths charming. I saw them as a set of largely incomprehensible nonsequiturs, not even good fairy tales. This reaction, of course, is a function of the vast alienation between modern western, and premodern Amazonian life. But what should I take from that?

“Thereupon, Pareni and her husband, Yagontoro, became alarmed. Wasn’t Pachakamue upsetting the order of the world with the words he uttered? The prudent thing to do was to kill him. What evils might come about if he went on speaking? They offered him masato. Once he’d gotten drunk, they lured him to the edge of a precipice. “Look, look,” they said. He looked and then they pushed him off. Pachakamue rolled and rolled. By the time he got to the bottom, he hadn’t even waked up. He went on sleeping and belching, his cushma covered with masato vomit.” (p. 133).

At least we can say that human beings are distinguished from the numerous birds, monkeys, insects, cats, and cows that populate the book, in one main feature: alone among the animals, we tell stories to each other.