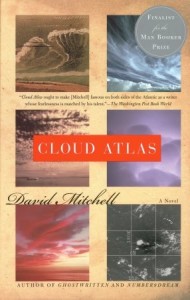

Mitchell, David (2004). Cloud Atlas. New York: Random House.

Robert Frobisher, a character in one of the six novellas that make up Cloud Atlas, is a composer in 1931 Europe who describes his new work in a letter to a friend. It is a “’sextet for overlapping soloists’: piano, clarinet, ‘cello, flute, oboe, and violin, each in its own language of key, scale, and color. In the first set, each solo is interrupted by its successor: in the second, each interruption is recontinued, in order. Revolutionary or gimmicky?” (p. 445).

Well, gimmicky, is my judgment, although that does not rule out thought-provoking and clever. But revolutionary? I don’t think so. It’s an experimental novel that plays with structure rather than content as its innovation.

Like Frobisher’s musical sextet, each of the six stories presented does have its own language, setting, and time, and its own population of characters. Each story is also interrupted abruptly, sometimes in mid-sentence, by its successor. The sixth story, however, the keystone in the arch, finishes uninterrupted. Then each of the first five stories, in reverse order, resumes from where it left off.

The first story is presented as the journal of a 19th century gentleman on a commercial ship operating somewhere around New Zealand. The language is archaic, as if were from Moby Dick. The traveler has various adventures, until his story simply stops in mid-sentence at the bottom of a page. We assume that the rest of the journal pages were missing. However, the author provided no context for interpreting the interrupted diary – no prologue, no introduction, no framing device, so the abruptness of the interruption is unexplained, and the reader may feel abused.

Robert Frobisher begins the second story, also epistolary, like the first. We are presented with a succession of letters he wrote to his friend and lover, a young man named Sixsmith back in London. We learn that Frobisher is a well-educated dandy and musical prodigy. He writes imperiously and cynically to Sixsmith about trying to hustle a living on the continent. His last letter is dated September, 1931, ending his story without resolution. Again the reader is left unsatisfied. There might be additional, missing letters, but without context, one’s reaction is, “What is the point of this?” We have seen this trick once already, so it is not as shocking as it was for the seaman’s diary, but still, we are left wondering, why does David Mitchell insist on showing himself like a flasher in the park? Why can’t he just tell a straightforward story we can believe in?

The third story is a thriller, set in 1970’s Pennsylvania. Naturally, I do not expect it to end properly and I start reading very much expecting the rug to be pulled out, but I figure it is going to be much harder for him to trick me this time. This is a straight narrative story and he wouldn’t dare end it in mid-sentence with no explanation. Wary, I read on.

The plot moves along with fairly good, albeit clichéd suspense: a reporter discovers a huge safety problem at a nuclear reactor. The problem is being covered up by greedy and murderous executives. She gets the incriminating documents and is speeding away from the nuclear plant when she drives off a bridge into an ocean bay sixty feet below and her car sinks. The End. The author has flashed me again!

The game continues. The fourth story is ostensibly a memoir, of a man held captive in an old folks home. Every once in a while, the narrator violates the memoir form to address the reader directly, such as, “You probably spotted it pages ago, dear Reader.” What does it mean? It is just the author flashing again. The story comes to an abrupt end. I expected it, of course, but it comes in a goofy, childish manner. The character says, “…and then I died.”

Story number five is set in the future. It is a sci-fi tale, with special, “futuristic” language. Evil overlords have enslaved all workers. The format is again epistolary, the supposed transcript of an interview with one of the workers who was a key figure in a failed revolution. The end of the transcript comes as the height of the action and intrigue are described, and is abrupt, but more reasonable than the previous ones.

The center story of the book is a weird tale in a post-apocalyptic future earth, set in Hawaii. The narrator uses a strange, invented dialect, hard to read, but not as difficult as the previous story’s language. It is as if Huck Finn spoke a Hawaiian Islander’s pidgin. The tale meanders over one thing and another while the narrator indulges in neo-romantic speechifying. Nothing happens and the story ends normally.

Subsequently, the five previous, interrupted stories pick up where they left off and finish. But why bother reading them? Isn’t the game up at this point? Essentially yes. The stories themselves are not very good, even if you can remember how each started, so there is little dramatic drive to get you through the last half of the book. Nevertheless game methodically plays out to the last line of the last (and first) story, when all the music falls away and the sextet ends on a single, quiet note.

Interesting? Extremely, but only if you are a writer and care about the normally hidden mechanics of how stories are told. The stories themselves are mundane and clichéd, illuminating nothing, overwritten, and being all chopped up, difficult to follow. If you enjoy being jerked around by a novelist who violates the implicit contract between writer and reader, and if you don’t mind an author jumping out of the narrative to flash himself at you, the book can be recommended.