Pouty Financial Analyst Goes Home

Pouty Financial Analyst Goes Home

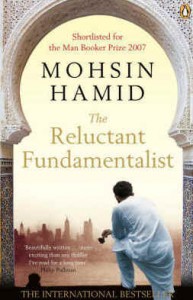

Hamid, Mohsin (2007). The Reluctant Fundamentalist. New York: Mariner/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Most novels are written in either third-person or first-person voice Second-person is rare, and there is a good reason for that: it’s clunky. Hamid’s Reluctant Fundamentalist is written in the second-person. Here’s how it opens:

“Excuse Me Sir, but may I be of assistance? Ah, I see I have alarmed you. Do not be frightened by my beard: I am a lover of America.”

The narrator talks to some other person (the second person), who does not talk back. Another version of second-person occurs in advertising, where the Other is “you,” the reader/consumer: “You will experience glorious sunsets and tropical breezes. You will relax like never before.” When second-person narration is directed at you, the reader, it quickly becomes preachy, authoritarian, and tedious (as advertising does). We can ignore that version of second-person in this context.

What does second-person do for us in literature? Like first-person, it is somewhat intimate, as the only voice is that of the narrator. But since that narrative voice is directed at another character, it gives the reader the feeling that he or she is eavesdropping. It seems to me that second-person is a blend of first- and third-person with the advantages of neither.

However, one thing second-person does well is silence the Other. Only the narrator can speak. The Other cannot talk back. In Hamid’s book, the Other is an American in Lahore, Pakistan, sitting at a café. He is joined by the narrator, a Pakistani named Changez (“Chongas”). It is a sometimes tense conversation, between a Pakistani and an American just after the 9/11 attacks. With second-person narration, the result is not an argument, not even a dialog, but a monologue. The American voice is silenced, giving the Pakistani voice all the air time it wants to make its case, which is what Changez does over the course of 185 pages.

So I can appreciate Hamid’s artistic choice to use the second-person voice, but I still say it makes a clunky narrator and I fought it throughout, especially in the passages where Changez attempts to bring the American Other to life:

“Do you see those girls, walking there, in jeans speckled with paint? Yes, they are attractive. …”

That reminds me of old Bob Newhart recordings in which we only got one side of a telephone conversation: “What’s that you say, President Lincoln? You’d rather go to the theater tonight? I don’t know if that’s such a good idea.” And I kept getting images of the old Lassie TV show: “What is it, Lassie? Timmy has fallen down the well again?”

Changez’s story is ostensibly an autobiography. He earns a full scholarship to Princeton, where he fits in with his American classmates. He falls in love with one of them, Erica, but their relationship remains Platonic. I assumed that Erica stands for Am-erica, and that the relationship is allegorical.

After college, Changez gets a high-paying and prestigious job at a consulting firm that does financial evaluations of businesses about to be bought or sold. He is a star performer because he learns to examine a company’s fundamentals. The title of the book ostensibly refers to that financial “fundamentalism”, coyly disguising the religious and political variety. Religious fundamentalism does not enter explicitly into the book but is implied.

Changez is unable to consummate his relationship with Erica because she can’t get her mind off her recently deceased boyfriend, and is unable to “get into the mood” with the man right in front of her. Allegorically, America dwells in its past colonial glory, unable to face the new realities of the world in front of it. In the finest scene in the book, Changez suggests to Erica that she pretend he is the dead boyfriend and sure enough, that works and they make love.

It is a humiliating situation when the only way your girlfriend can be with you is if she pretends it is not you. And worse, it was his suggestion: I want to be admitted so badly that I’ll deny my personal identity and become some other person you are more comfortable with, if that’s what it takes. Is that what America is asking Pakistan to do on the world stage today?

Changez begins to realize that while he is superficially admired, he is in fact not accepted into the inner circle of American society, presumably because of his ethnicity. Any westerner who has traveled in Asia will recognize this feeling. People are polite, generous, and cordial, but you feel, you know, that you will never, ever, be admitted to what’s really on people’s minds. There is an inner life and an outer life, and the foreigner will never get past the foyer, regardless of appearances and actions that say otherwise.

Changez slowly begins to realize this about himself in America, and resents it. Finally there is an epiphany, provoked by a fellow named John the Baptist (get it?). Changez quits his job, leaves America, and returns to Lahore, embittered.

Why is he embittered? Because he fell in love with New York, Princeton, America, and Erica, then realized he would never be fully accepted, then he fell out of love. His reaction seems naïve and petulant, greatly disproportionate to his experience. Toward the end he rants on about the blindness, bigotry, and stupidity of Americans, individually, institutionally (e.g, harassment while traveling), and in international politics. There is some truth to his ravings, but for the most part they are exceptionally naïve. Xenophobia and ethnic bias in America after the 9/11 attacks? Who could have seen that coming?

My feeling is that Hamid’s intention was literally to “give voice” to a Pakistani’s view of American culture (without letting the American talk back), in order to point out how America’s arrogant sense of entitlement is hurtful, personally and internationally. So Changez’s story boils down to a cross-cultural diatribe that for me was heavy-handed and simplistic. Changez is clearly a mouthpiece for the author. The story, falling into and out of love with America, is blasé.

It would have been a much better story, I think, if Hamid could have used his considerable skill in showing subtle shifts in psychology, to demonstrate how an intelligent, Americanized character like Changez could reasonably and logically become a virulent and violent Islamic extremist. Some of that is mildly and distantly intimated near the end, almost as an afterthought. The excellent movie adaptation of the novel handles this aspect much better (and dispenses with the second-person voice).

There is such a wide gulf between ordinary Americans and violent Islamists, it could have been helpful and fascinating to show a transformation from one into the other. Instead, what we have is that Changez feels slighted so goes home to pout. A disappointment.