Clueless People Behaving Badly

Clueless People Behaving Badly

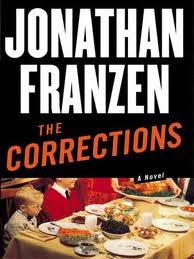

The Corrections

Jonathan Franzen. New York: Farrar Strauss and Giroux, 2001

This saga of Midwest family life put Franzen on the map, as did its selection for Oprah’s Book Club (the kiss of death), which he controversially declined at the last minute for fear of alienating male readers. But I think it alienates anyone with an ounce of intellect, regardless of gender.

The story (or saga, for there is no story, really), is about an ordinary, middle-class family in contemporary Ohio. The pathetic, small-minded, egocentric, undersocialized, developmentally arrested, morally questionable lives of family members are explored in a quasi-humorous way by a judgmental, omniscient narrator, who seems to take the tone, “Aren’t ordinary human foibles a hoot?” Well, no, Mr. Narrator, they’re merely pathetic, small-minded, etc., and boring.

Patriarch Al is retired from the railroad and does some amateur chemical engineering in his basement, but now suffers quickly advancing dementia. Matriarch Enid has no discernible skills, talents, education or interests, has apparently never held a job, and devotes her full time and energy to maintaining the common manipulative motherly delusion that she is the center of the universe.

The book has no chapters, but is divided into large sections, one for each of the three children, and one devoted to Enid and Al. So this 600 page novel is a compilation of four novellas, linked by family relationships over the course of about a year.

The Failure is Chip’s section. He is a college professor at a small New England school where he struggles to get his awful screenplay finished for a New York publisher. (How he gets the time of day from a New York publisher is a detail I must have missed). He succumbs to the charms of a sexy female student who offers him an ecstasy-like drug, Mexican A, leading to a weeks-long sex-fest, for which Chip is busted when the student goes public, and he is disgraced and fired from the college, just as in Coetzee’s novel, Disgrace, but I’m sure that’s only a coincidence. He tells his parents he is a writer in New York, but actually he is broke, borrowing from his sister to scrape by as a bum. His publisher’s editor connects him to an online writing job in Lithuania. What could be funnier than Lithuania?

Brother Gary’s section is called The More He Thought About It, the Angrier He Got. He lives in Philadelphia, I think, is a banker with a rich wife and some kids. He and his wife have nothing but acerbic contempt for each other. She constantly reminds him that he is depressed, and he accuses her of manipulative lying. Gary acts like his father, and his portrayal of his wife echoes his mother. He tries to “manage” his parents, bullying his father to sell his implausible invention, a new Prozac-like drug, Correcktall. Al refuses. Gary badgers his mother to sell the house and move into assisted living. She refuses.

The section, At Sea, belongs to Al and Enid, as they take a cruise from New York to somewhere Caribbean, I think it was. Cruise ships are an easy satirical target and Franzen goes positively DeLillo to demonstrate that, but without much insight, his observations fall flat. On the cruise, Enid gets an anti-anxiety drug from the ship’s quack doctor, a drug whose description is similar to Mexican A. Al falls overboard and nearly drowns but is rescued. What a scream.

The Generator is the name of a section of the book, and a restaurant that Denise works in as a high profile chef. The restaurant is owned by rich friend, Brian, and his wealthy wife, Robin. Denise is severely neurotic (like her mother) and sexually dysphoric. She had married and divorced a chef and now seduces Brian, then Robin. In flashback, we learn that in college she also seduced another married man. Anyway, having seduced Robin, Denise becomes jealous of Brian and seduces him again, but Robin walks in on them. Could happen to anyone, really.

The convergence of these stories occurs in the section One Last Christmas, where the siblings gather at the parents’ house in Ohio for predictable cruel and histrionic infighting – a typical family Christmas in lowbrow America? Al has a gun in his basement shop, but don’t worry, that’s a red herring. And he ultimately did not take the Prozac-like Correcktall that he partly invented. Enid scores another stash of Mexican A, but has second thoughts and flushes it, so no worries there. The carefully laid-in theme of mind-altering drugs thus amounts to nothing. Al has is by now reduced to an incoherent pissing and pooping machine. Hilarious, or merely tragic? In this section Franzen lets the reader know (twice), in case the reader is particularly dim-witted, that this story is supposed to be a tragedy rewritten as farce. That’s true of the book’s publication also.

While characterization and plain old story-telling are sorely lacking in this novel, there are pockets of excellent wordsmithing. Franzen is particularly good at presenting long lists of well-selected objects or situations that effect sharp phenomenological observation. He is good at the unexpected but telling detail. So there is craftsmanship here, but it just doesn’t add up to anything. The human condition he apparently intends to illuminate is one that Woody Allen only needed one line to capture: “My brother thought he was a chicken, but we were nice to him because we needed the eggs.”