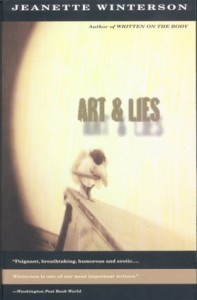

Winterson, Jeanette. (1994). Art & Lies. New York:Vintage

Idly, I picked up this book in a used book shop. The publisher’s blurb on the back said it was “…a daring novel that burns with phosphorescent prose on every page.” I thought, “Yeah, sure.” I opened the book at random and to my amazement, every page I read burned with phosphorescent prose.

Is it a novel? Not in the Aristotelian sense. There is no plot, no storyline, no climax, no epiphany, no denouement. But there is life-drama, mystery, strong characterization and beautiful language. In fact the work could be read as a series of extended prose-poems.

Alternating chapters describe the lives of the three main characters, Handel, a physician-priest, Picasso, a young woman who paints, and Sappho, the pre-Socratic poet of sexuality. The three lives mildly intersect from time to time, unknown to the characters. A fourth, minor, enigmatic character who does not get her own chapters, is an aging prostitute searching for her boyfriend/john/pimp.

All these characters are on a train, going to their future, fleeing their past. The train represents the arrow of time that moves each character through their lives. Sappho, the ancient poet, represents herself, with a lifespan of 2500 years. Picasso is not Pablo, just a young woman with that moniker, and Handel is not the 18th century composer, just a guy named Handel, (Although the prostitute’s sought-after boyfriend is named Ruggerio, a character in an opera by Handel the composer). In Handel’s life story, I had a sense of 19th century England, but other allusions, especially in Picasso’s story, place us at least in the 20th century. The location seems vaguely European. So: no fixed time or place.

The characters are fleeing themselves. Handel is trying to escape and forget a tragic surgical mistake in which he amputated the wrong breast in a botched mastectomy. That cost him his career. He’s also trying to escape his childhood, which involved long-term sexual abuse by a Catholic priest who nevertheless genuinely loved and educated him.

Picasso, literally running away from home, flees a childhood of incest forced on her over the years by her brother, and a tyrannical, dismissive family, and attempted suicide. She seeks to lose herself in her painting but may be losing her mind.

Sappho is the most difficult character. She resents that her poetry has been misunderstood or bowdlerized through the centuries. She claims to be a pure sexualist, not a romantic, not a metaphorical poet. “Say my name and you say sex,” she says. Sex alone is her topic, including its inevitable deceptions. She pontificates, beautifully, on the nature of art, despairs at the lack of passion in modern life, but it is not clear what her “mission” is, or from what, if anything, she flees. Her chapters are dreamlike.

I should read this book again, two or three times. It is laden with allusions, historical, and inter-textual references. Alas, life is too short. Based on a single read, my thought is that the title reveals the controlling theme: Art and Lies. Those are the only two elements that drive a life. The embodied life, is full of lies, lies mostly about sex. But the mundane life of the flesh is transcended in art, which spiritually lifts one to another plane.

The three biographies demonstrate this theme. In Sappho’s case, the lyrical language is so intense, it intoxicates the reader, proving by direct demonstration that art lifts one above the plane of flesh. That’s a brilliant innovation.

Here are samples, selected literally at random, of the kind of writing that drew me in:

Handel: “I like to look at women. That is one of the reasons why I became a doctor. As a priest my contact is necessarily limited. I like to look at women; they undress before me with a shyness I find touching…When a woman chooses me above my numerous atheist colleagues we have an understanding straight away. I have done well, perhaps because a man with God inside him is still preferable to a man with only his breakfast inside him.”

Picasso observes: “On the dark station platform, lit by cups of light, a guard paced his invisible cage. Twelve steps forward twelve steps back. He didn’t look up, he muttered in to a walkie-talkie, held so close to his upper lip that he might have been shaving. He should have been shaving. Picasso considered the guard; the pacing, the muttering, the unkempt face, the ill-fitting clothes. In aspect and manner he was no better than the average lunatic and yet he drew a salary and was competent to answer questions about trains.”

Sappho prefers: “To carry white roses never red. White rose of purity white rose of desire. Purity of desire long past coal-hot, not the blushing body, but the flush-white bone. The bone flushed white through longing. The longing made pale by love. Love of flesh and love of the spirit in perilous communion at the altar-rail, the alter-rail, where all is changed and the bloody thorns become the platinum crown.”

The prostitute is described in third person: “Doll Sneerpiece was a woman, and like other women, she sieved time through her body. There was a residue of time always on her skin , and, as she got older, that residue thickened and stuck and could not be shaken off.”