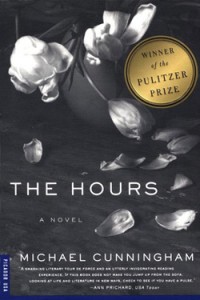

Cunningham, Michael (1998). The Hours. New York: Picador USA

Fan fiction rarely gets published, but Cunningham’s The Hours somehow managed it. Fan fiction is written by fans of characters in stories created by someone else. A fan-writer produces elaborations and alternatives based on the established characters for fun and for the amusement of other fans, who presumably have read the original.

The Hours is Cunningham’s homage, to use a more generous term, to Virginia Woolf’s classic novel, Mrs. Dalloway. In the original 1925 novel, Clarissa Dalloway was an upper-class London matron who considered socializing to be an art form. That novel shows one day in her life, shopping for flowers and preparing a dinner party for her husband, Richard. She clings to her status and refined sensibilities but secretly worries if she wasted her life by marrying wealth, rather than by choosing her youthful sweetheart, the unpredictable adventurer, Peter, or even the wild and irreverent Sally, her childhood girlfriend. Mrs. Dalloway’s anxiety about her life choices as she faces aging and death, animates the novel.

In The Hours, Clarissa Vaughan is a 1990’s New York woman who is called “Mrs. Dalloway” by her friend and former lover, Richard, a renowned poet dying of AIDS. She is seen buying flowers and preparing a dinner party for Richard. Is she conflicted about her life choices, as was the original Mrs. Dalloway? Yes, because the narrator says so: “…she is now revealed to herself as a meager spirit, too conventional, the cause of much suffering.”

A fundamental flaw in The Hours is that the narrator tells us what characters feel and believe, without much, or any evidence. Woolf’s novel was an exercise in stream-of-consciousness writing, in which the reader had direct access to the characters’ thoughts and feelings. Cunningham is not much interested in stream-of-consciousness, so his narrator just declares what characters think and feel. The result is hollow.

In modern writing an author often bridges a character’s stream-of-consciousness to a narrator’s description using a method called free indirect discourse, in which the narrator’s voice merges with the character’s voice from time to time, but Cunningham executes the method poorly, as in this example:

“She isn’t jealous of Sally, it isn’t anything as cheap as that, but she cannot help feeling, in being passed over by Oliver St. Ives, the waning of the world’s interest in her and, more powerfully, the embarrassing fact that it matters to her even now, as she prepares a party for a man who may be a great artist and may not survive the year. I am trivial, endlessly trivial, she thinks.”

The first sentence is the voice of the narrator, inside Clarissa’s head. The second sentence is Clarissa’s voice. I find the passage clunky, in part because of Cunningham’s choice of a first-person present narrator, which makes the narrator merely voyeuristic rather than authoritative about characters’ inner thoughts, unlike Woolf’s first-person, past narrator.

Maybe Cunningham relies heavily on narrative telling rather than characterological showing because his story is so ambitious. There are two other major characters. Virginia Woolf is in 1923 London, struggling against depression on her last day, while writing her novel, “Mrs. Dalloway.” In the course of her ruminations, she decides that Clarissa Dalloway will kiss another woman (Sally), command tea and dinner tables as an art form, and not kill herself. The Mrs. Woolf character is only interesting to fans of the original novel and to readers who know Woolf’s biography, but taken objectively, it is the least interesting character in The Hours. Of course fan fiction necessarily rests on a foundation of wink-wink, nudge-nudge, so this is perhaps an unfair criticism.

The third main character is Laura Brown, a suburban housewife in 1949 Los Angeles who suffers from “feminine mystique syndrome,” mid-century middle-class conformity and meaninglessness. She is pregnant with her second child and we see her half-heartedly baking a birthday cake for her husband, because she must, and being secretly obsessed with the novel, “Mrs. Dalloway,” which she has half-finished. She has passionately kissed another woman (not Sally) and worries about that. Contrived though the character is, her life is the most well-observed of the three and for that, the most interesting:

“She loves her husband, and is glad to be married. It seems possible (it does not seem impossible) that she’s slipped across an invisible line, the line that has always separated her from what she would prefer to feel, who she would prefer to be. It does not seem impossible that she has undergone a subtle but profound transformation here in this kitchen at this most ordinary of moments: she has caught up with herself.”

If we ignore the narrator’s tendency to tell us what Mrs. Brown feels, rather than letting her speak or behave for herself, we can admit that this passage does spotlight a genuine and important existential moment, all the more so because in the context of having just baked a meaningless, sagging cake, we realize that her epiphany is essentially untrue: she is NOT happy to be married and she has NOT caught up with herself. That’s good stuff.

It’s worth noting also how Cunningham peppers his prose with parenthetical expressions as in the quote above, but fails to realize that in the original novel, characters’ behavioral action was backgrounded by putting it in parentheses, to emphasize the foregrounding of the stream of consciousness. In other words, Woolf had a purpose for all the parenthetical expressions, but Cunningham just uses them as window dressing.

Having read and enjoyed “Mrs. Dalloway,” I cannot un-read it, so it’s impossible for me to imagine what a naïve reader would get out ofThe Hours. There are many well-observed moments that might sustain reading. An example is when a character enters Clarissa’s and Sally’s apartment:

“Sally and Clarissa live in a perfect replica of an upper-class West Village apartment; you imagine somebody’s assistant striding through with a clipboard: French leather armchairs, check; Stickley table, check; linen-covered walls hung with botanical prints, check; bookshelves studded with small treasures acquired abroad, check. Even the eccentricities – the flea-market mirror frame covered in seashells, the scaly old South American chest painted with leering mermaids – feel calculated as if the art director had looked it all over and said, ‘It isn’t convincing enough yet, we need more things to tell us who these people really are’”