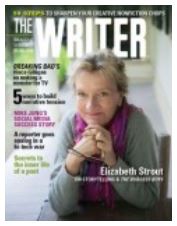

Elizabeth Strout is on the cover of the August, 2013 The Writer magazine. She has a new book, Burgess Boys, which I haven’t yet read. I enjoyed Amy & Isabelle, and I rank Olive Kitteredge as one of the greatest-ever collections of short stories, even though it’s marketed as a novel. I think it barely qualifies as a novel, since the unrelated stories have many of the same characters and the small-town setting is a constant.

What makes Strout distinctive is her command of the narrative voice. She writes mostly in third-person and the narrator is a participant observer, someone who was there when it happened, and tells how it was. It’s a very natural voice, what your buddy would use describing what happened on a fishing trip. He was there, as a participant and as an observer and he tells the story straightforwardly.

Here’s an example of Strout’s narrative voice, from the opening lines Olive Kitteredge:

“For many years Henry Kitteridge was a pharmacist in the next town over, driving every morning on snowy roads, or rainy roads, or summertime roads, when the wild raspberries shot their new growth in brambles along the last section of town before he turned off to where the wider road led to the pharmacy.

Retired now, he still wakes early and remembers how mornings used to be his favorite, as though the world were his secret, tires rumbling softly beneath him and the light emerging through the early fog, the brief sight of the bay off to his right, then the pines, tall and slender, and almost always he rode with the window partly open because he loved the smell of the pines and the heavy salt air, and the in the winter he loved the smell of the cold.”

The magic is the phrase, “Retired now, …” That’s the unnamed, quasi-invisible narrator telling you she knew Henry when he used to drive every morning to the pharmacy, and (shifting momentarily to present tense), she still knows him now that he’s retired. So we feel confident this narrator will tell us truly how it is with Henry, because she’s been involved for so many years. She pulls us deep into the world of the story in the first two sentences. It is writing magic.

When your buddy tells you what happened on a fishing trip, he’s standing right in front of you. You already have a relationship with him. You know how you feel about his reliability, intelligence, observational skills, insight. But you don’t know anything about the narrator of a literary story.

The literary narrator must establish her credentials, and Strout does it gently, subtly, without focusing attention on the narrator, without bumping you out of the story, which is about Henry, not the narrator.

A different approach would be for the narrator to start with a mini-resume to explicitly introduce himself to the reader. Yann Martel did that in Life of Pi, but I thought it was cloying overkill. Any first-person narrator can become boring or obnoxious even Phillip Marlowe, Chandler’s great detective. Tom Robbins had a very strong third-person narrator in Skinny Legs and All, but it was too strong. I quickly tired of the narrator’s self-aggrandizing cleverness.

Elizabeth Strout is the Goldilocks of narrative voice. Her narrator is not invisible as the narrator usually is in genre fiction, but not in-your-face either.like Tom Robbins’ narrator. Strout’s narrator is “just right.” There’s a lot more to Strout than narrative voice. Even the two sentences quoted above show that. But her voice is perfect and I would like to emulate it but I haven’t discovered how.