Margaret Atwood cut her writing teeth on poetry and it shows in her novel, The Blind Assassin, perhaps too much. Her phrases are carefully constructed, a virtue in any writer, but Atwood’s choices often stand out as slightly too clever, while not particularly insightful. As the book opens, the narrator’s sister, Laura, has died, and Iris, the sister, writes about her sister’s novel,

Margaret Atwood cut her writing teeth on poetry and it shows in her novel, The Blind Assassin, perhaps too much. Her phrases are carefully constructed, a virtue in any writer, but Atwood’s choices often stand out as slightly too clever, while not particularly insightful. As the book opens, the narrator’s sister, Laura, has died, and Iris, the sister, writes about her sister’s novel,

“Hard to fathom, in my opinion: as carnality goes it’s old hat, the foul language nothing you can’t hear any day on the street corners, the sex as decorous as fan dancers – whimsical almost, like garter belts.” (p 39)

I enjoyed “whimsical like garter belts” as a phrase, but what does it mean? Are garter belts whimsical? And even if they are, Laura’s sex scenes were “almost” that whimsical, meaning what? This is one example of hundreds and hundreds throughout this long novel, of phrases that catch your eye but on closer inspection are close to nonsense.

“Such a thin book, so helpless. The uninvited guest at this odd feast, it fluttered at the edges of the stage like an ineffectual moth.” (p. 40)

Arresting image, until you ask yourself what an “ineffectual moth” is. What would an effectual one be? And if you’re wondering why the narrator is still waxing on her sister’s novel, the answer is that Atwood waxes. That’s why the book is too long.

In long, excruciating backstory, we follow the lives of the two sisters from when they were wealthy teenagers in a small town in Eastern Canada, to the death of Iris, seven decades later. What happens between are the two world wars and the depression, with the appearance of soldiers, businessmen, love affairs, marriages, babies, households and the stuff of life. As in much “literary” fiction, nothing really happens. It’s just ordinary everydayness piled high and deep. Getting through the novel is, as a colleague commented, an Iditerod of reading.

More than half of the eighty or ninety short chapters open with a weather report, followed by detailed description of the scenery, and continue into long, lush descriptions of walks in the town or country, food and drink, shopping, clothing, babies and children. Such material may hold particular fascination for some readers, but it was suffocating for me.

Are there redeeming virtues? Yes. The novel did not win the Booker Prize for nothing. One interesting aspect is the narrative structure. The whole novel is presented as a diary, or letter, addressed to someone, we are not told whom until the very end. The ending is contrived and clichéd, swooping into the final few pages like a Deus ex Machina.

Within this long diary, Iris, the ostensible writer and first-person narrator, tells the story of her difficult lifetime relationship with Laura, her wild sister who died in the first chapter in a car accident that always smelled of suicide. Interspersed throughout the diary is a novel, called The Blind Assassin, supposedly the novel that Laura wrote. It is a cheesy sci-fi adventure, written in third person narration, and involves swordplay, monsters, space travel and foreign worlds. It is stereotypical nonsense, badly written, clichéd, and pointless. However, the astute reader notes it would take considerable skill for someone like Atwood to deliberately write that badly on purpose, so it is interesting in that regard – only.

Finally, the embedded novel, The Blind Assassin is not simply inserted into The Blind Assassin, but rather told as a story, or a series of stories by an unnamed man who claims to be a writer, to an unnamed woman, who we guess is Laura. The point of view narrator for that part seems to be Laura, who asks the man repeatedly to continue with the story. But what is Atwood’s point of view on that point of view? That’s an interesting and tricky question that is not adequately dealt with, making the structure an interesting piece of experimental writing which in the end, breaks the implicit contract with the reader that says third-person narrators are always reliable. Still, I give points for the effort.

Another virtue of the novel is Atwood’s skill at finely detailed description of fixed scenes and especially of photographs. Atwood seems drawn to ekphrasis, a poetic term for written description of a picture or a work of art. The book opens with a vivid description of a photograph and that is a recurring theme. Ekphrastic writing tries to “tell a story” about a photo, film, or painting, a type of writing that is well-suited to Atwood’s narrative voice.

Finally, as mentioned, much of Atwood’s descriptive writing involves highly poetic language. Taking an arbitrarily selected 154-word paragraph …

“Today I had something different for breakfast. Some new kind of cereal flake, brought over by Myra to pep me up: she’s a sucker for the writing on the backs of packages. These flakes, it says in candid lettering the color of lollipops, of fleecy cotton jogging suits, are not made from corrupt, overly commercial corn and wheat, but from little-known grains with hard-to-pronounce names — archaic, mystical. The seeds of them have been rediscovered in pre-Columbian tombs and in Egyptian pyramids; an authenticating detail, though not, when you come to think of it, all that reassuring. Not only will these flakes whisk you out like a pot scrubber, they murmur of renewed vitality, of endless youth, of immortality. The back of the box is festooned with a limber pink intestine; on the front is an eyeless jade mosaic face, which those in charge of publicity have surely not realized is an Aztec burial mask.”

We notice it is pure description, a propos of nothing, as so much of the book is, and one is tempted to skim right on past with annoyance. But if a reader were to take the time to notice, some lovely constructions are buried in that pile of verbiage:

“candid lettering the color of lollipops” is a visual, vivid, creative, and original phrase well-worth savoring.

“Candid lettering, ” color of lollipops:” 2 syllables followed by three, 2x(trochee + dactyl), with alliteration! Not bad at all. The rhythmic nature of the phrasing is no accident and such constructions do not grow on trees. The astute reader must whisper, “Bravo!”

Is such a construction necessary, or even desirable in a book that’s supposed to be a novel, a “dramatic” tale (though it contains no drama) where story is supposed to be king? That is a separate question.

“fleecy cotton jogging suits” is another fine phrase — I can almost hear the band playing that tune. Say it out loud and you’ll enjoy it. And it invokes both tactile and kinesthetic senses to boot.

“corrupt, overly commercial corn and wheat” — less good, but still nice.

“little-known grains with hard-to-pronounce names”

On this one, she should have said “difficult” instead of “hard-to-pronounce.” Try it out loud both ways. Is my version too obvious?

Some of Atwood’s phrases are visually arresting, even when not especially rhythmic:

“festooned with a limber pink intestine” — “festooned” is a lovely word, but followed by that particular noun phrase, well, it grabs you in the eyeballs (if not the guts).

So overall, I say that this 154-word paragraph does pay its rent, but that does not mean it should have been included in this novel. Rather, it could be construed as self-indulgent wordplay that shows contempt for a reader vainly searching for a story.

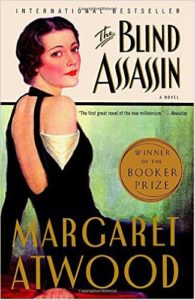

Atwood, Margaret. (2000), The Blind Assassin. New York: Doubleday/Anchor (518 pp.).