When does a sequence of scenes not make a story? A good story is driven by causality: incident A causes incident B, either by the laws of physics, or by plausible character actions.

When does a sequence of scenes not make a story? A good story is driven by causality: incident A causes incident B, either by the laws of physics, or by plausible character actions.

In Joe, much of the text is a series of episodic vignettes as the character is painted as an illiterate ex-con in 1970’s rural Mississippi. He smokes cigarettes, he drinks, he has sex, he drives around in his battered pickup, he goes to the store. We get a picture of an angry but listless Faulknerian lowlife living in whatever county is next to Yoknapatawpha. But these events add up to just one damn thing after another.

Brown is aware of the Faulkner legacy and imitates the master in evoking southern-gothic life, but since Brown’s characters are supposed to be more contemporary and realistic than Faulkner’s mythic subhumans, the imitation falls flat. Brown’s characters are simply stupid, disagreeable and uninteresting. Brown does play the pronoun game Faulkner loved so much, beginning chapters with illegitimate definite articles and vague pronouns so you don’t know what’s going on for a few paragraphs or pages. I hated that in Faulkner and it isn’t any better in the hands of Brown.

Joe may not be the main character of the book anyway. The only spark in the tale is in the story of the young boy, Gary, who Joe hires as a manual laborer on his forestry crew. Gary is utterly uneducated and unsocialized, feral, really, and yet inexplicably has a refined ethical sense. Joe becomes a kind of protector for the boy because Gary’s father is an unalloyed bad person who lacks only a mustache to twirl. As a cartoon bad guy he is far more annoying than interesting.

Finally, near the end of the book, Joe takes a decisive moral action, almost impulsively, against a mild antagonist, and that is supposed to be the cathartic climax, but by that point, this reader was in advanced “who cares” mode.

The writing in Joe is often poetic, although pointless descriptions of the landscape drag on for meaningless paragraphs. No matter how finely wrought, descriptions of landscape and weather do not propel a story, unless they are specifically designed to do so (e.g., in The Martian, to use an extreme example). There was a time when writing merely for the sake of fine writing was acceptable to readers. That time has passed.

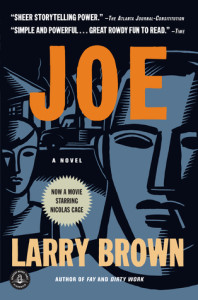

I should add that the book was miraculously made into a decent movie starring Nicholas Cage, the only movie since Moonstruck in which Cage shows he really can act.

Brown, Larry (2003). Joe. North Carolina: Algonquin Books. (345 pp).