Recently I’ve been reading some of the classical Greek plays, notably Aeschylus: Agamemnon, The Persians, and Seven Against Thebes; Sophocles: Ajax. I took a couple of Classics courses in college and enjoyed them, and this re-visit broadens my understanding.

Recently I’ve been reading some of the classical Greek plays, notably Aeschylus: Agamemnon, The Persians, and Seven Against Thebes; Sophocles: Ajax. I took a couple of Classics courses in college and enjoyed them, and this re-visit broadens my understanding.

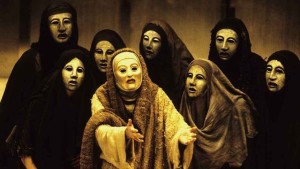

I’ve been especially interested in the role of the chorus in Greek theater. They were a group of six to twelve singers who stood together, up front near the orchestra. They engaged in musical dialog with the actors.

I’ve learned as much from the introductions to the plays by scholars and translators as I have from the plays themselves. Apparently, the chorus represented the wisdom of the community, and were typically presented as old women or old men (all played by men though, of course).

In the beginning, Greek theater was the chorus and nothing else. Basically a choir would sing and chant music and poetry for the entertainment and edification of the audience. Sophocles was himself a prize-winning conductor of boys’ choirs.

Over time, as the parts in the choir became differentiated, a lead singer would take a solo and engage in a sort of musical conversation with the rest of the choir. Eventually, the lead singer separated from the choir and stood alone on the stage. That was the first actor and Greek theater was born.

In most fifth-century (BCE) plays, there are only two or three actors, who converse with each other and the chorus. In a very funny section of “Seven Against Thebes,” the main character, Eteocles, becomes annoyed with the chorus and orders them to shut the hell up (which they won’t). But that’s unusual. Mostly, the chorus articulates the feelings and thoughts of the community, giving the main actor an opportunity to speak indirectly to the (idealized) audience.

I wonder if the device of the chorus is a literary structure that could be revived in modern literature somehow. I tried to do something like that in my first novel, “Hunter and Hunted,” (www.bit.ly/Hunter-Hunted), with limited success. It seems there should be a way to have the reading public explicitly represented in the story.

We don’t really have a way for characters to address the reader directly any more, nor a way for the audience to talk back to the main character. Yes, we have the clunky second-person point of view, where the main character addresses “Dear reader.” Nabokov managed it well in Lolita, and a few others have, but usually that second-person voice quickly devolves into a traditional, word-spewing first-person narrator. Is it a loss for us to not have a literary structure where the characters can address the reader directly?

We also don’t have a way for the reading audience (as represented) to address the main character directly. What we do is create a so-called “reaction character” whose story purpose is to say to the protagonist things like “Don’t do it, Harry! It’s a bad idea!” But do such reaction characters really represent the reading audience?

The community seemed well-represented in speaking against Hester Prynn in The Scarlet Letter, but in the end, after Dimsdale was exposed, we saw that the community’s scorn might have been misplaced. I can’t think of a good example of where community feelings and thoughts about the main character’s actions are well-represented in modern literature.

Maybe a chorus seems too heavy-handed anymore. Let the character act and encounter glory or doom as it happens, and that’s the story. What the audience thinks, or should think, is not in the equation. Think whatever you want about the character and his story. If you’re unsure, join a book club.

Is that where we are now? Has pluralism evolved to the point where it is no longer possible or desirable for fiction to edify an audience? If that’s so, what is an author’s responsibility? Simply to entertain? Shouldn’t every novel then be a book of jokes?

Maybe we’re at a place in literature where authors are no longer authoritative. “If you want to send a message, send a telegram,” said Samuel Goldwyn, with the implication that modern storytelling is not about sending messages. What is it about then?