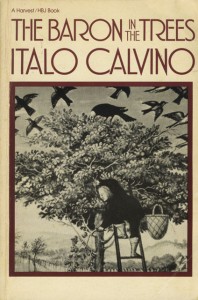

Calvino, Italo (1959). The Baron in the Trees. New York: Random (217 pp).

In 1767, a 12-year-old Italian boy climbs a tree and vows never to come down. And he never does. Living the rest of his 50 years in the trees, he learns to travel far and wide in a thickly forested Europe, branch to branch, never touching the ground again. In the early chapters we learn how he adapts to arboreal life, hunting food, building shelter, staying clean, dry, and warm. He meets people, who think him strange, but he is friendly and articulate. He takes part in village life, falls in love, travels with thieves, fights off pirates, takes a lover in Spain, reads books, writes letters, helps with the grape harvest, and leads a revolutionary movement. It’s a charming fantasy, told in anecdotes, with no over-arching plot. Eventually he gets old and dies.

The story is told by his younger brother, an odd device, because his brother did not accompany the arboreal baron in his adventures so could not, as a practical matter, report them. He claims he is telling what his brother told him, or surmising what must have happened. A standard, third-person narrator would seem to have worked better. For much of the book, the brother fades away and the narrator is functionally a 3P anyway. Perhaps having the brother intrude from time to time helped keep the story from floating away in pure fantasy.

Besides the delightful fantasy of a boy, then man, living in the trees, is there any point to this novel? Two main elements stand out. One is that by living in the trees, the young man (of a minor Italian aristocratic family – when his father dies, he inherits the title of Baron), rejects the status quo. He spurns the aristocracy and his own family. He lives outside normal human society. He literally looks down on other people. He chooses freedom over conformity, despite the ridicule he must endure, the creature comforts foregone, the strained relationships with everyone, especially the love of his life, Viola.

The Baron in the trees rejects civilization, but does not turn his back. He does not become a feral animal. He helps the villagers, fights pirates and bandits, writes books, leads discussions. Right about when this book came out, Calvino left the Communist party, declaring that it had become something he could no longer participate in. So maybe there’s some of that sentiment reflected. The Baron rises above the conventions of civilization, but does not forsake his humanity. Only a madman thinks he can escape society.

The second major element is the time frame. The Baron enters the trees in 1767, and dies in the early 1800’s, so he experiences the French Enlightenment, the French revolution, the Napoleonic wars, the Reign of Terror. He corresponds with Voltaire and Denis Diderot. The message seems to be that despite the noble ideas of the Enlightenment, especially those about the sanctity of individual freedom, which the Baron emphatically chose, human beings will never change. They will continue to steal from and kill each other, armies will wreak destruction, politicians will be venal, peasants will struggle in bewilderment and in the end, you die anyway. Freedom does not redeem life. Not even love redeems life.

The book falls into the category of “a fun read,” with plenty of good humor and delightful invention, but since there is no character development and no overall dramatic development, it amounts to a well-written, allegorical fairy tale with historical, cultural, and political allusions. I’d recommend it to any high school student.