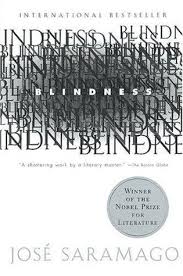

Saramago, José (1995). Blindness. New York: Harvest.

A man sits in his car at a traffic light, staring at the red, waiting for the green. The light turns green and the cars around him roar ahead. But not his. Angry drivers behind honk their horns. Some come forward to abuse him in person. But he waves his arms and cries, “I am blind!”

He’s only the first. One by one, characters suddenly go blind, without warning, without cause. Their visual field is filled with impenetrable, uniform white, so the epidemic is called the white blindness. It spreads across an unnamed city and an unnamed European country.

The main characters are, ironically, an ophthalmologist and his wife. The doctor examines newly blind patients, consults medical books, but can find no explanation. Then he goes blind. Inexplicably, his wife does not.

The government sets up quarantines, hoping to stop the contagion, and the doctor, along with his wife, who pretends to be blind, are shipped off to an empty insane asylum, along with a few others. Soon the place is full beyond capacity and they are surrounded by soldiers with orders to shoot anyone who approaches the exit.

The center of the book concerns the blind inmates’ experiences in this prison, their deprivations, the filth and degradation, the starvation, inhumanity, and violence. The story morphs from a Camus-like Plague story to a description of a concentration camp. This part of the story continues far too long. It takes about ten pages to understand the Holocaust analogy, but the sordid action goes on and on.

Finally, in the last quarter of the book, the internees escape into a devastated, post-apocalyptic world in which groups of ragged, filthy blind people stagger among corpses lying in the streets, like zombies searching through destroyed and looted stores for any remaining food and water. The ending is completely manufactured and quite disappointing.

The writing is thoughtful and well-observed, but reportorial, rather than poetic. The narrator does the reflecting, describing scenarios, and character’s thoughts and feelings, because the characters themselves are generally too busy just trying to stay alive. Having the doctor’s wife as the only sighted person is a brilliant device that allows Saramago to contrast blind and sighted experience throughout.

The book’s typographic style seriously detracts from the reading. Punctuation, other than the comma and the occasional period, is non-existent. One is confronted with long, often page-long, strings of run-on clauses, perhaps suggesting that for a blind person, experience is not well-organized. Quotation marks and dialog tags are not used, so it’s usually difficult to tell who’s speaking, presumably as it would be for blind people in a crowd. It’s a clever but unnecessary gimmick, adding little more than an obstacle to reading enjoyment. On top of that, the narrator promiscuously shifts point of view among characters and himself, and often spontaneously migrates through all the grammatical tenses, for no apparent reason. So this book is not an easy read.

Thematically, we are repeatedly thumped over the head with descriptions of man’s inhumanity to man. People are mean, thoughtless, selfish, greedy, cruel, brutish. Take away the thin veneer of civilization and vicious, hairless monkeys are revealed. Once in a while a word, or an act, of compassion or courage shows up like a beacon at sea (that nobody can see). This obvious theme has been worked many times. Lord of the Flies comes immediately to mind, but there are plenty of others. This book contributes no new insight on the topic, and renders the whole middle section of the book tedious.

What I enjoyed was the observant phenomenology of blindness, although there wasn’t nearly enough of that for my liking. For example, in one scene a man has cut himself and is bleeding badly, but because he is blind, he doesn’t notice at first, and when he realizes he is bleeding he is annoyed, but not horrified or panicked. The reader takes pause to realize how significant the sight of blood is in reacting to injury. In other insightful scenes, a blind person touches fingertips to a mirror, trying to feel his reflection; a bad man threatens a crowd with a handgun, but he’s blind, and so are the others, so what, exactly, is the nature of the threat; blind people have trouble washing and using the toilet; they form relationships based on talk and gesture, but not on looks; they despair at the now-useless art museums in the world. A writer describes how he uses a ball-point pen to slightly emboss his paper so he can tell where he’s written and where the page is still blank, but he can’t answer the question of why he does it, there being no readers left in the world, and you think about how useless the world’s libraries and televisions and computers, and movie theaters and smartphones would be if everyone were blind. These, and similar observations about the central place of vision in life, are consistently fascinating.

Less fascinating, and really, not even believable, are characters’ (and the narrator’s) squeamish shyness about nudity. What does nudity even mean if everyone is blind? That question was apparently too difficult to address properly so its awkward handling stands out. Another issue too difficult to even question, is what it means to “own” a house if all of civilization has broken down, including law enforcement, monetary economics, and contract law. Characters mindlessly seek to “return home,” and squabble over who owns what. Other problems arise if you take the story too literally. Anyone with an ounce of problem-solving skill could have solved many of the difficulties the characters faced. So the story does not mean to create a literal dystopic world, because it fails in that. Rather, the white blindness is a contrivance to focus our attention on what kind of human nature underlies the surface of polite society, and on how fragile human relationships are, yet without the delicate spider-web of convention, how we would all become selfish brutes. In that sociological, psychological aspect, the book is more successful, but not particularly insightful.

Saramago, who died in 2010, won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1998.