Getting Small

Getting Small

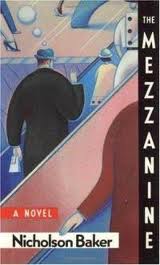

Baker, Nicholson. (1988). The Mezzanine. New York: Grove Press.

This strange little book (107 pages) is the stream of consciousness of a generic office worker in a generic company in a generic American city in the 1980’s. He comments on his sensations and experiences, and relates them back to his childhood and to changes in American industrial design. His comments are thoughtful, often humorously faux-naïve, phenomenological reflections on life’s little mysteries and frustrations, like how difficult it is to find a new pair of shoelaces of the right length, style, and color.

His office is on the mezzanine floor of a building and he reflects repeatedly, obsessively, on escalators: how they look, how they work, their aesthetics, their dangers, his childhood memories of them, how they compare to airport baggage conveyors, and dry cleaners’ conveyors; the intrinsic beauty of their grooved steps and comparison to the grooves on the ventral side of the sperm whale, and the grooves in vinyl records.

He talks about office carpeting, the frustration of taking the last piece of tape from a tape dispenser, the pleasures of refilling a stapler. He gives an excellent analysis of tying a bow in a shoelace, which, when you think about it, is a remarkably complex skill.

“Howie,” the office worker is called, remembers his delight upon ordering his first rubber stamp; he comments on sliced olives in cream cheese, the demise of home milk delivery, and how to put on deodorant without removing your shirt (related to how women remove a bra without removing their shirt). He is impressed by the technological innovations in public rest rooms. He is nostalgic for cigarette machines, paper straws, and the aluminum foil that once wrapped sticks of gum.

The fun of the book is the extreme attention to tiny detail. Every writer knows how difficult it is to “get small” and look, really look at the world, and how easy it is instead to write vague abstractions. So it is not only enjoyable, but instructive to get small with the author. The tiny details are often described in poetic language, which illustrates even further how much reflection the author put into each tiny aspect. Many ordinary objects and practices are described in so much detail that you wouldn’t think it possible to say another word about them. Then you notice a footnote, which continues the discussion in a “digression” that can run over a page, although what counts as a digression and not as just another thought in Howie’s chaotic stream of consciousness, is arbitrary.

On the downside, Howie is a one-trick pony. He has a knack for extreme close up observation and excellent phenomenology, but little else. We learn next to nothing about him, who he is, where he comes from, what he believes, what motivates him, what he wants, what he looks like. He is presented to us only as an associative flow of linguistically sophisticated, intellectual conceptualizations. One’s clinical impression is that he is mentally disturbed, possibly suffering from mild Asperger’s syndrome, possibly comorbid with OCD.

The endless free-association does become tedious, even in such a short “novel,” if that’s what this book is. Some serious questions are raised, but not analyzed or resolved, such as the nature of nostalgia and how it differs from sentimentality. He implicitly questions our fascination with industrial design and marketing of consumer technologies, but says no more than that. The deadness of office life is well-evoked, almost as succinctly as in Roethke’s poem, Dolor, which begins, “I have known the inexorable sadness of pencils, Neat in their boxes, dolor of pad and paper weight, All the misery of manilla folders and mucilage, Desolation in immaculate public places.”