Amateur Detective with Tourette’s

Amateur Detective with Tourette’s

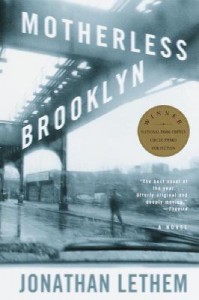

Lethem, Jonathan (1999). Motherless Brooklyn. New York: Random/Doubleday.

The “Motherless” of the title is a group of four teenage boys living in an orphanage in 1979 Brooklyn. They are hired out for odd jobs of questionable legality by Frank Minna, a local small-time thug and mobster wannabe. The first-person narrative is given by one of the boys, Lionel Essrog, a fifteen year-old who has Tourette’s syndrome, a neurological disorder characterized by outbursts of verbal free-associations and rhymes.

Frank gets killed and the rest of the book is Lionel’s story of searching for the murderer. So it is nominally an amateur detective tale, but as such it is extremely weak. Instead, the novel should be read as a completely original character study and as a virtuosic display of literary writing talent. Here are some samples:

[Frank’s mother,] Carlotta Minna was … a cook who worked in her own apartment, making plates of sautéed squid and stuffed peppers and jars of tripe soup that were purchased at her door by a constant parade of buyers… When we were in her presence Minna bubbled himself, with talk, all directed at his mother, banking cheery insults off anyone else in the apartment, delivery boys, customers, strangers (if there was such a thing to Minna then), tasting everything she had cooking and making suggestions on every dish, poking and pinching every raw ingredient or ball of unfinished dough and also his mother herself, her earlobes and chin, wiping flour off her dark arms with his open hand. …Carlotta hovered over us as we devoured her meatballs, running her floury fingers of the backs of our chairs, then gently touching our heads, the napes of our necks. We pretended not to notice, ashamed in front of one another and ourselves to show that we drank in her nurturance as eagerly as her meat sauce (pp. 70-71).

“Want one?” he said, holding out the bag. His voice was a dull thing where it began in his throat but it resonated to grandeur in the tremendous instrument of his torso, like a mediocre singer on the stage of a superb concert hall.

“No, thanks,” I said…

“So what’s the matter with you?” he said, discarding another of the withered kumquats.

“I’ve got Tourette’s,” I said.

“Yeah, well, threats don’t work with me.”

“Tourette’s,” I said…

He shoved me again, straight-armed my shoulder, and when I tried, ticcishly to shove his shoulder in return I found I was held at too great a distance…and it conjured some old memory of Sylvester the Cat in a boxing ring with a kangaroo. My brain whispered, He’s just a big mouse, Daddy, a vigorous louse, big as a house, a couch, a man, a plan, a canal, apocalypse.

“Apocamous,” I mumbled, language spilling out of me unrestrained. “Unplan-a-canal. Unpluggaphone.” (pp. 203-205).

Lionel’s verbal tics are creative and often funny, designed by Lethem with poetic rhythm and sonority. This keeps the recurring gag from getting stale as the novel wears on. Also, as the example shows. Lethem gives us access to Lionel’s thought processes so when he utters his verbal outbursts, we understand, as other characters in the story cannot, meaning the outbursts might have. I confess that after the first half of the book, the Tourette’s gimmick began to wear pretty thin for me. However, the quality of the writing remained very high, excellent narrative descriptions, snappy dialog, and interesting, quirky characters and settings. So even though the book is not entirely successful as a detective story, and not consistently funny as a humorous tale, the writing is so good the book carries you to the end.